Hungarian Filmlab shines a light on its photochemical pipeline for 'Son of Saul' and film archiving services

As the name suggests, Magyar Filmlabor, The Hungarian Filmlab, has celluloid experience coursing through its veins. For more than 60 years the company has provided prestige film-processing services to all manner of filmmakers.

So when it came to supporting the desire of director László Nemes and his cinematographer Mátyás Erdély HSC for a pure, end-to-end, photochemical finish on KODAK 35mm film for Son Of Saul, the team was eager to rise to the challenge. The success of the project was such that Son Of Saul garnered a staggering 47 wins at film festivals worldwide and sparked fresh business opportunities for the lab amongst local and incoming filmmakers.

Hungarian Filmlab was established in the 1950s and is still wholly-owned by the Hungarian government. The facility, which was merged with Mafilm Studios in 2013 under the administration of the Hungarian National Film Fund, is located in the Buda district of Budapest. Its flourishing celluloid operations provide a full range of services to filmmakers and content owners worldwide, including 16mm add 35mm color and B&W negative processing with push/pull processing, 16mm/35mm neg cutting and film color timing, as well as release prints and back-to-film archiving.

“Film has always been and remains a crucial part of our business operations,” says Hungarian Filmlab senior colorist and company marketing manager Szabolcs Barta. “Although we have no way of knowing about a production’s eventual box office success, we believe all movies are good and perform as professionally as possible in our support to them. Because of the solid funding we receive and our status in maintaining the heritage of the Hungarian filmmaking industry, the facilities here are amongst the best-equipped and most modern you will find anywhere. And our clients are supported by a team that has huge amount of analog film experience.”

The company has been the natural magnet for Hungarian filmmakers throughout its long history, with hundreds of domestic titles on an ever-lengthening credit list. Notable amongst these are Ferenc Rófusz’s 1980 animated short The Fly (A légy), István Szabó’s Mephisto (1981) and Son of Saul (Saul fia) (2015) – all of which turned out to be Academy-Award winners. Other local, Oscar-nominated productions include Szabó’s Colonel Redl (1985) and Hanussen (1988). The lab’s credentials extend far beyond Hungary’s borders, attracting the likes of Israeli film director Joseph Cedar with his Oscar-nominated productions Beaufort (2007) and Footnote (2011).

Image from "Son Of Saul", directed by László Nemes, shot by cinematographer Mátyás Erdély HSC. Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics.

“We are now seeing a younger generation of filmmakers looking for something unique and turning to film for the answer,” says Barta. “So we were hugely excited when László and Mátyás approached us with the idea of supporting a full photochemical film workflow on Son of Saul.”

Image from "Son Of Saul", directed by László Nemes, shot by cinematographer Mátyás Erdély HSC. Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics.

Son of Saul marked the feature debut of director Nemes. Set amid the horrors of the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp in 1944, the film centers on Saul Ausländer (played by Géza Röhrig), a Hungarian-Jewish man who works with the Sonderkommando, a supposedly privileged workgroup comprising of prisoners who dispose of the bodies of those slaughtered in the gas chambers. When he finds the body of a young boy who he thinks is his son, Saul is driven to search for a Rabbi in the camp to conduct a formal funeral.

Image from "Son Of Saul", directed by László Nemes, shot by cinematographer Mátyás Erdély HSC. Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics.

The $1.5 million production shot for 28 days in Hungary on four-perf 35mm VISION3 500T 5219 filmstock using Zeiss Master Prime lenses. Featuring long takes (there are only 85 shots in the 107-minute film) and a camera style that stays with Saul in close-up for almost the duration of the movie – apart from fleeting glimpses of life and death incidents – Son of Saul earned an impressive cluster of top accolades. These include the Grand Jury Prize at the 2015 Cannes Film Festival, and best foreign language film at the 2016 Oscars and Golden Globes. Erdély gained recognition for his efforts at the world’s leading cinematography events with a Golden Camera 300 at the Brothers Manaki International Film Festival, Bronze Frog from Camerimage, plus the ASC’s Spotlight Award.

Géza Röhrig as Saul. Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics.

Hungarian Filmlab processed a total 28,000m/92,000ft of 5219 35mm negative for Son of Saul, “a rather modest figure, given that larger budget productions often shoot three times this volume,” says Barta. Using 5219, Erdély felt he could maintain consistent grain structure and contrast from the production through to the photochemical finish and the final release prints. In order to have a slightly higher contrast and more speed for all the night exterior scenes, he worked closely with Hungarian Film lab on one-stop, push processing for this material.

During production, Nemes and Erdély viewed projected film dailies everyday, with Erdély’s color timer Viola Regéczy and Hungarian Filmlab’s DI grader László Kovács also in attendance.

“We were after an image that was raw and brutal, and to carry through the concept of everything looking neutral,” comments Erdély. “It was truly amazing to be such a small-budget, Hungarian, first-feature film and still go to the lab and watch our printed dailies. We were blown away by the power of the projected film images.”

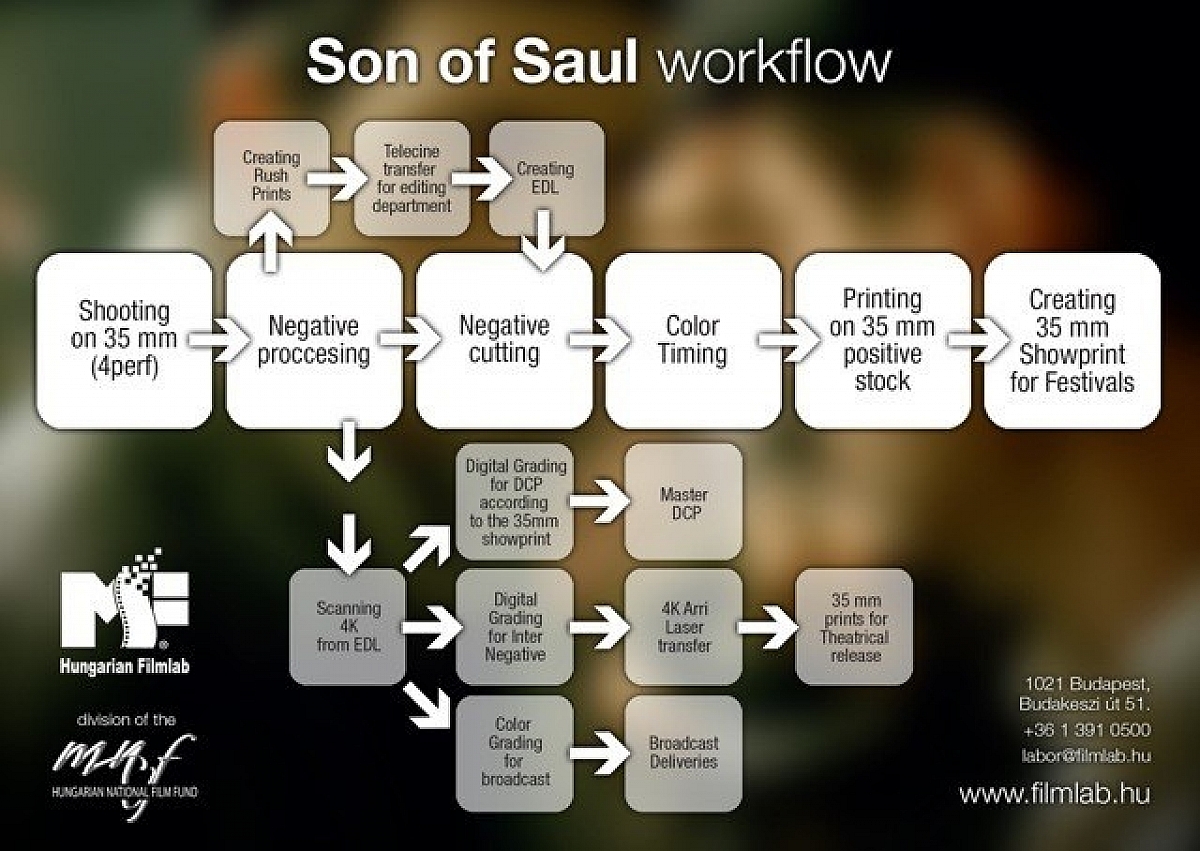

Once the takes from the rush prints had been selected, Hungarian Filmlab set about the process of neg cutting, followed by color timing under Regéczy’s auspices, before making final prints on 35mm for release at festivals worldwide. Indeed, Nemes and Erdély screened a 35mm print, struck from the cut camera negative, at the Cannes Film Festival. Along with the 35mm pipeline, Hungarian Film Lab also created a DCP for screenings where a digital print was required, created by colorist Kovács by matching to the 35mm print.

“We had not done an end-to-end film workflow like this for several years and rediscovered what a soulful, collaborative and rewarding process it is,” says Barta. “Naturally, we are delighted by the success of the process on Son of Saul and the film’s subsequent triumphs around the world.”

Working from 100-year old original camera negative, Hungarian Filmlab restored and archived back-to-film Michael Curtiz’s 1914 production "The Undesirable."

Barta says the overall impact of Son of Saul’s success on other filmmakers making Hungary their destination has been considerable. “After seeing the results on the big screen in Cannes, when the French production HHhH, about the Czech resistance operation in WWII, came to shoot in Hungary, they used us for their 35mm film processing. We have been fielding more and more enquiries from local filmmakers wanting to take advantage of film ever since, too, and we’re very keen to show them how shooting on film can pay you back big time.”

Along with servicing feature productions, Hungarian Filmlab has also developed a reputation for film restoration and film archiving. In 2013, the company took receipt of a tinted positive print of the 1914 production The Undesirable, one of the early works by Casablanca director Michael Curtiz, and was responsible for restoring the footage and shooting the results back-to-film for long-term preservation.

Working from 100-year old original camera negative, Hungarian Filmlab restored and archived back-to-film Michael Curtiz’s 1914 production "The Undesirable."

“For us, this project proved there is no doubt about the longevity of film, nor its inherent beauty,” says Barta. “Whilst we think the print of The Undesirable may have been one hundred years old, the images still had lovely details in highlight and the black areas that only film truly offers. The restored result looks great and it’s wonderful that the end result was shot back to film for preservation. The worry when you archive digital files is that they might not be readable in the future – so you’re potentially entrusting precious assets to a black hole. We all know that no light comes from a black hole, unlike film, where all you have to do is shine a light through it.”