Captured on Kodak, Steve McQueen’s 'Widows' is a heist movie with a surprising heart

Liam Neeson and Viola Davis in Twentieth Century Fox’s "Widows", directed by Steve McQueen. Photo Credit: Courtesy Twentieth Century Fox. Copyright: TM & © 2018 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation. All Rights Reserved. Not for sale or duplication.

Shot on Kodak 35mm, Widows is no ordinary Hollywood heist movie. Directed by Steve McQueen and shot by his long-time cinematographic collaborator Sean Bobbitt BSC, the Chicago set feature contains high-octane car chases and menacing violence, but it also connects to a diversity of contemporary themes, including poverty, police brutality, corruption, interracial marriage, sexism and racism.

Developed by McQueen and co-written by him and Gillian Flynn, Widows is based on the 1983 ITV series of the same name by Lynda La Plante. McQueen was a young admirer of that series and was impressed with the daring of its female characters. Transporting the story from London to modern-day Chicago, McQueen’s Widows follows a group of women who attempt a heist after their criminal husbands are killed during a botched job, only to find themselves brutally exposed to the same vicious and malevolent world their deceased spouses inhabited.

Widows is the fourth feature that Bobbitt has shot for McQueen, following Hunger (2008), Shame(2011) and the Oscar-winning 12 Years a Slave (2013) – with all four having been shot on 35mm film. It features an ensemble cast including Viola Davis, Michelle Rodriguez, Elizabeth Debicki, Cynthia Erivo, Colin Farrell, Robert Duvall and Liam Neeson.

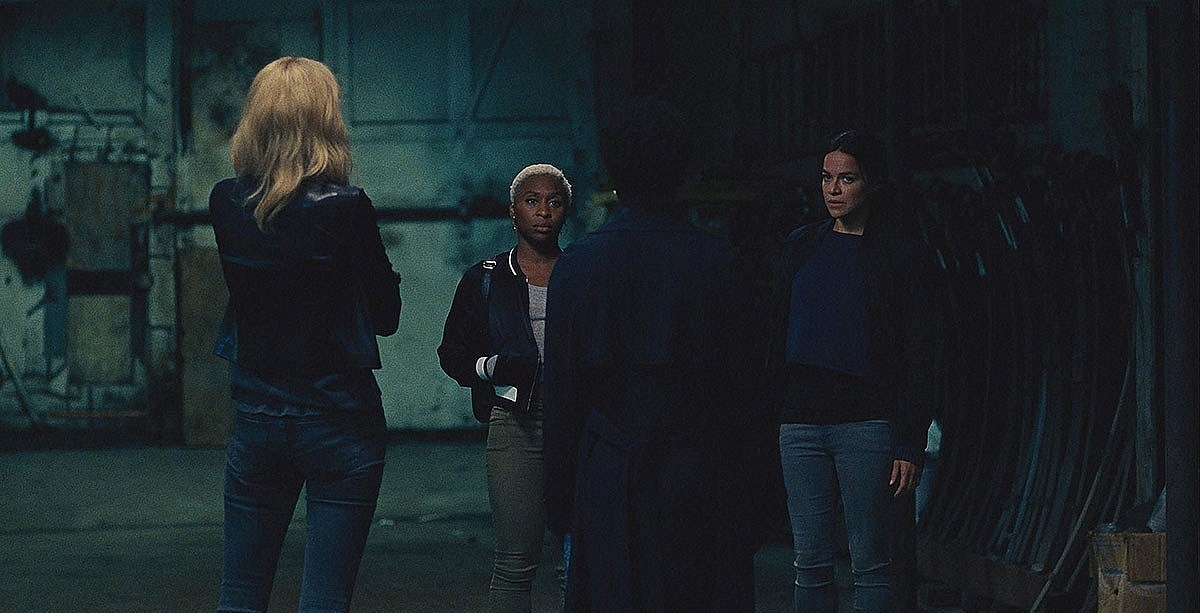

(l-r) Elizabeth Debicki (back to camera), Cynthia Erivo, Viola Davis (back to camera) and Michelle Rodriguez star in Twentieth Century Fox’s "Widows". Photo Credit: Courtesy Twentieth Century Fox. Copyright: TM & © 2018 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation. All Rights Reserved. Not for sale or duplication.

“I had never been to Chicago before and was immediately impressed by the physical architecture,” recalls Bobbitt about his early immersion into the project. ”However, it is also quite remarkable in the way that it has extremes – such as inordinate wealth and desperate impoverishment – pretty much side-by-side.

“Our original thinking for Widows was to take in Chicago’s physical structure and cityscape. But as we went along, the complexity and intensity of the story superseded the concept of including Chicago in that way. It became much more about the exposition of the people and their motivations than the architecture.”

He adds: “Film has been something that Steve has consistently insisted on in all our previous work together, which is based on what it does best – storytelling. It remains a better acquisition medium than digital, and it stores more information in the negative. Additionally, when film is combined with digital post, you get the best of both worlds in terms of the final quality of the image and the power to tell a story.”

Daniel Kaluuya and Brian Tyree Henry in Twentieth Century Fox’s "Widows". Photo by Merrick Morton. Credit: Courtesy Twentieth Century Fox. Copyright: TM & © 2018 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation. All Rights Reserved. Not for sale or duplication.

Production on Widows took place at locations around Chicago for 11 weeks, starting in April 2017 and concluding in June. Mainly a single camera shoot, Bobbitt variously deployed ARRI LT and ST 35mm cameras, fitted with his preferred Cooke S4 lenses, shooting on Kodak 35mm celluloid and framing the action for a 2.40:1 extraction.

During production Bobbitt operated, supported by Christopher Flurry as 1st AC, Summer Marsh as 2nd AC, and Matt Hedges as film loader. David Chameides operated Steadicam and also photographed second unit beauty shots of Chicago.

Cinematographer Sean Bobbitt BSC pictured on-set filming Twentieth Century Fox’s "Widows", directed by Steve McQueen. Photo Credit: Merrick Morton. Copyright: TM & © 2018 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation. All Rights Reserved. Not for sale or duplication.

Speaking about the visual approach to Widows, Bobbitt says, “Having worked closely with Steve for so many years, we have spent a lot of time together discussing films, as well as art, photography and TV. When we come to consider a new project, we very quickly focus on what the story is and how best to portray it.

“In this case we referenced American epics, such as Chinatown (1974, dir. Roman Polanski, DP John A. Alonzo), to see how big, complex stories had been told in the past, whilst looking for simplicity in the storytelling. Typically, we wanted to create strong image compositions within which the actors could find their performances. We also wanted to convey the story of a scene without having to shoot extraneous coverage. Consequently, we kept the blocking and camera movement as simple as possible and went for a naturalistic look to the lighting.”

A dramatic moment in Twentieth Century Fox’s "Widows". Photo by Merrick Morton. Credit: Courtesy Twentieth Century Fox. Copyright: TM & © 2018 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation. All Rights Reserved. Not for sale or duplication.

Bobbitt says he and McQueen came up with some visually intriguing and unexpected framing devices to shoot familiar generic scenes and go beyond typical cinematic exposition.

For example, while the film opens with an explosive car chase sequence, the action is intercut with a God’s-eye view of mobster Harry Rawlins (Liam Neeson) and his wife Veronica (Viola Davis) kissing passionately in bed. The conversation between would-be politician and local crook Jamal Manning and his violent henchman Jatemme is framed through glass, with the fractured picture reflecting light from the blue tiles and brown wooden panels of the interior.

In another scene, the audience listens in to a long conversation taking place in a car about criminal violence in Chicago, whilst the camera surveys the journey from in front and above the vehicle, sharply depicting the economic differences between Chicago’s precincts and neighborhoods.

To capture the action, Bobbitt went with three 35mm film stocks – KODAK VISION3 50D Color Negative Film 5203, VISION3 250D Color Negative Film 5207 and VISION3 500T Color Negative Film 5219 – keeping the lighting naturalistic and seeking a richness of color but without the images being overly saturated. Film processing was completed at Fotokem in Los Angeles.

“Shooting in Chicago in the spring and early summer, it can be very sunny and bright,” Bobbitt says. “So my first choice was the 50D. It’s really a wonderful filmstock with great characteristics – low grain and abundant natural color. I used it for all of the daylight exteriors and daylight interiors when I could get away with it. Otherwise I used the 250D for daytime interiors, and as it gave an extra stop, and I knew it would cut well with the 50D.

(l-r) Michelle Rodriguez, Viola Davis and Elizabeth Debicki star in Twentieth Century Fox’s "Widows". Photo Credit: Courtesy Twentieth Century Fox. Copyright: TM & © 2018 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation. All Rights Reserved. Not for sale or duplication.

“Traditionally, most heists take place at night, and the dramatic heart of this film was no different. We shot the night interior and exterior scenes using the 500T. Its latitude and ability to capture scenes in very low-light have never failed to amaze me. I could open up by a stop or two on set or increase the sensitivity by push-processing the 500T at the lab without any concerns of adversely affecting the color saturation or grain.”

Bobbitt adds, “But the quality of modern Kodak film stocks is quite astounding in another way, and this helped enormously on Widows. Back in the day, if you had actors with light and dark skin in the same scene, you would, more often than not, have to light up the dark skin – which could be complex and time-consuming. Not so these days. Viola (Davis) and Elizabeth (Debicki) are both on the extreme ends of the exposure range, but I never had a problem in balancing the light and keeping them perfectly exposed on set. When we came to do the final grade at Company 3, we could see that, having used film, the rendition of their individual skin tones in the same frame was exceptional.”

Cinematographer Sean Bobbitt BSC pictured on-set filming Twentieth Century Fox’s "Widows", directed by Steve McQueen. Photo Credit: Merrick Morton. Copyright: TM & © 2018 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation. All Rights Reserved. Not for sale or duplication.

As many cinematographers attest, Bobbitt also enjoys the inherent discipline that film imposes upon production. “When the first AD calls ‘Turn-over,’ everyone is focused and concentrating. Each of the actors and the crew know the onus is on them to get their part right. And when the call comes to ‘Cut,’ it offers a natural break for everyone. So often these days with digital, the director will keep the camera going and just ask for a reset. In this instance, people can lose concentration. Overall, it’s counter-productive and ultimately wasteful as someone, somewhere has to manage and process all of that digital data.”

Reflecting on the final outcome of his work on Widows, Bobbitt says, “It was another happy and fruitful collaboration with Steve. People see Steve, quite rightly, as a master art-house filmmaker. On this occasion, it was a joy to help bring that masterful experience into a traditional studio thriller – to balance entertainment with some proper substance and to deliver a movie that really stands out though commanding performances and some surprising visuals. I am really so glad that we captured all of that on film.”