Rising DP Ziryab Ben Brahem harnesses VistaVision for his eye-catching short 'The Negative'

© Ben Brahem, Mate Boegi.

Passion can take you places. Never was this truer than of up-and-coming DP Ziryab Ben Brahem, a recent graduate in cinematography, whose eagerness to shoot on film saw him trekking into the American wilderness with a VistaVision camera in hot pursuit of capturing dream visuals for his short film The Negative. The result is stunning, leaving viewers impressed and his academic contemporaries perhaps a little covetous of his achievement.

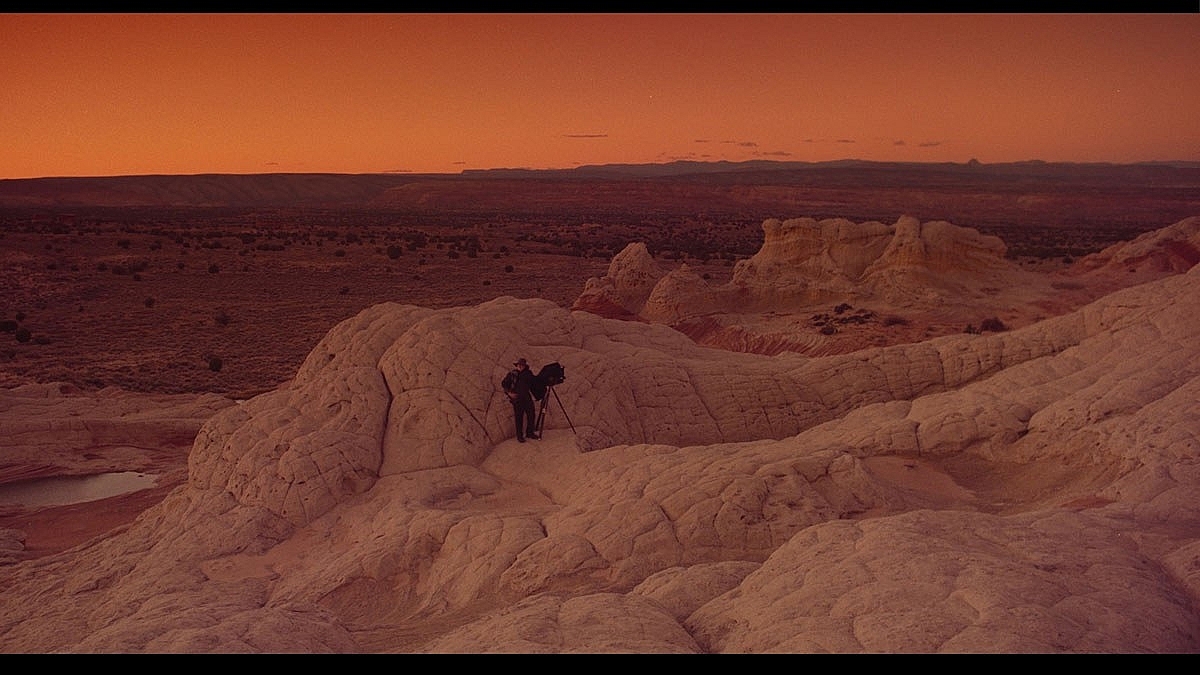

The Negative observes an aging photographer who sets out with a plate camera to capture his final masterpiece in the arid, rocky outcrops of the American West. However, the landscape proves so vast and wild and beautiful, that he quickly despairs ever being able to emulate the natural beauty in front of his eyes. Until, that is, he spies an ant, which causes him to reflect on his place in the cosmos. This comforting moment of revelation frees the old man from his frustrations and enables him to take his ultimate photograph.

“I had the idea for The Negative as my 2015 thesis film project for quite a while. It was very visual with no dialogue, although I was not sure how to make it work cinematically,” said Brahem, who studied at San Diego State University. “I had no money either and was really uncertain as to how I would solve the challenges of getting it made.”

Actor John Greenleaf, who plays the photographer, stands next to his 8x10 large format camera at White Pockets, Arizona. Photo by Mate Boegi.

As luck would have it, the student DP had earlier submitted his 16mm short, entitled Wake, into Kodak’s Student Cinematography Scholarship and won. It yielded him $3,000 worth of Kodak film stock and a small bursary towards his tuition fees. This break, plus a small amount of additional funding from the film school, brought him to a place where the project began to seem viable.

“Originally, I was planning on framing in a widescreen format on 35mm. But I went to 70mm film presentations of The Searchers and Vertigo and was struck by the immersive experience and level of image detail in those films, which is exactly what you need when you want to shoot a landscape. After a little research, I discovered both movies were shot on 35mm but in VistaVision. This got me to thinking about how I might possibly use the same format for The Negative. But where to start?”

The crew waits for the perfect light at Monument Valley near Moab, Utah. (Photo cred: David Harvilla)

VistaVision was originally created by the film technicians at Paramount in 1954 as a large-format attraction to counter the perceived threat of television. The 35mm filmstrip runs horizontally through the camera, as opposed to vertically, with the sprocket holes above and below frame. This arrangement delivers a frame-width of 8-perforations and an overall frame size that is double the normal 35mm photographic frame, yet with an almost identical 1.5:1 (3:2) aspect ratio. As the camera system uses spherical lenses, the result is a high-resolution film format without image distortion.

Paramount introduced VistaVision at Radio City Music Hall in New York on October 14, 1954 with the debut screening of White Christmas, directed by Michael Curtiz. Other renowned filmmakers of the era fell in love with the quality of the images produced by VistaVision, most famously Alfred Hitchcock who used it for To Catch A Thief (1955), Vertigo (1958) and North By Northwest (1959); John Ford who produced The Searchers (1956) in VistaVision; and Charles Walters who used it for MGM’s hit musical High Society (1956).

DP Ziryab Ben Brahem and co-director Mate Boegi set up a shot using a Kessler camera slider modified for the weight of the VistaVision camera. Photo by David Harvilla.

VistaVision, though, went into near-obsolescence as four-perforation formats – including CinemaScope and Anamorphic – became the preferred choices for big screen entertainment by Hollywood studios since they used less stock in cameras and projectors. However, VistaVision’s high-resolution properties meant it has enjoyed widespread use in more recent years in special effects by directors such as Christopher Nolan who employed the format for set-piece action sequences in The Dark Knight and miniature work in Interstellar.

Enthused and on a mission to find a VistaVision camera, Brahem’s initial search led him to Los Angeles rental houses who, although impressed by his zeal, were not immediately willing to loan out their equipment. Undaunted in his quest, Brahem plucked up the courage to contact Greg Beaumonte, legendary developer of the Beaumonte VistaVision camera system, amongst other filmic contraptions, now based at 32TEN Studios in San Rafael, California.

“I called Greg, explained my project and lack of funds. But low-and-behold, he agreed to let me have a camera, magazines and a set of Leica lenses,” Brahem declared. “He dispatched the equipment to Los Angeles and then kindly spent time on the phone over a couple of days to take us through the physical mechanics of the VistaVision system. His support and goodwill were absolutely tremendous, and I would not have been able to make this film without his generous assistance. It was quite a thrill to know we would be using a camera whose provenance includes the spectacular explosion of London’s MI5 building in 007 James Bond SPECTRE.”

1st AC Jose De Matos and DP Ziryab Ben Brahem move the equipment to the shooting location at Horseshoe Bend near Page, Arizona. Photo by Mate Boegi.

After also going to some length to obtain special shooting permission from Navajo reservation chiefs, production on The Negative took place over the course of three ultra-long long days in the striking landscapes of Utah near Moab. Getting to the right locations saw the cast and crew – producer/second AC, David Harvilla, first AC Jose De Matos and co-director Mate Boegi, plus actor John Greenleaf – strenuously hiking for several miles in 100° F heat with the camera equipment and Kodak filmstock in backpacks. Included in the expedition was an ARRI 235 35mm camera (offered by DP Patrick Loungway) as a second camera for tight filming locations. The beauty of the Beaumonte VistaVision camera is that it can be readily fitted with ARRI 235 and 435 film magazines.

“Although I knew the place would be lovely, I don’t think any of us were quite prepared for the awesome spectacle there, especially the rich gradation of colors in the sunsets and sunrises. I wanted The Negative to be naturalistic, to shoot in available light, and to capture the colors and natural beauty of the landscape as part of an immersive experience. You could never hope to record that so perfectly with digital.”

1st AC Jose De Matos with his hands inside of a changing bag while loading a VistaVision film magazine. Photo by David Harvilla.

Brahem selected KODAK VISION3 50D Color Negative Film 5203 for the day exteriors, with VISION3 250D Color Negative Film 5207 deployed for scenes filmed in caves. “As we were shooting in VistaVision, I wanted the cleanest possible film look, and Kodak daylight stocks complement each other very well in this respect,” he explained. “Most of the film is set outdoors; the 50D was our workhorse. It has fine texture with luscious color rendition, especially on skin tones. And the color separation on sunrise and sunset scenes cannot be paralleled.

“The 250D has exceptional dynamic range and allowed us to shoot in dark caves with no artificial light and also at night with just a campfire for illumination. It captures details in the highlights and dark areas of the image without any problems, and the results are fantastic. Despite the rugged logistics of getting to our locations, plus the heat, the cameras and both films performed flawlessly.”

© Ben Brahem, David Harvilla, Mate Boegi.

Film processing for The Negative was done by Cinelab in Massachusetts. The 35mm 8-perf VistaVision negative was color-timed and then scanned at 6K for online editing, under the auspices of Robert Houllahan – although the company is cutting film prints for projection at festivals worldwide, including, Brahem hopes, a slot at the 2017 Venice Film Festival. “Film projection is the most intimate way to watch a film,” he noted.

On completion of his film, Brahem has naturally been eager to show others the fruits of his labours, including the distinguished cinematographer Ed Lachman ASC.

© Ben Brahem, David Harvilla, Mate Boegi.

As for his academic peers, Brahem remarks: “At film school, some of my contemporaries were skeptical about my passion for film. Some thought I was actually going backwards. But having seen the results of The Negative in VistaVision, they acknowledged an aesthetic that is quite remarkable, and it has piqued their interest in shooting on film, too. If my experience is anything to go by, I would say to anyone who also wants to shoot on film, ‘Follow your passion’. The film renaissance is in full swing, and there is plenty of support out there. All you have to do is ask.”