DP Robert Yeoman used Kodak color and B&W 35mm filmstocks for director Wes Anderson’s ‘The French Dispatch’

"THE FRENCH DISPATCH." Photo Courtesy of Searchlight Pictures. © 2020 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation. All Rights Reserved.

Director Wes Anderson is one of the most cherished of auteurs working in independent movie-making today, whose celluloid-originated features interweave intriguing narrative threads with star-studded casts and off-beat visual styling to relate quirky and highly-entertaining human stories. Shot on Kodak 35mm color and B&W filmstocks, by regular cinematographer Robert D. Yeoman ASC, Anderson’s next and highly-anticipated comedy, The French Dispatch, promises more of the same.

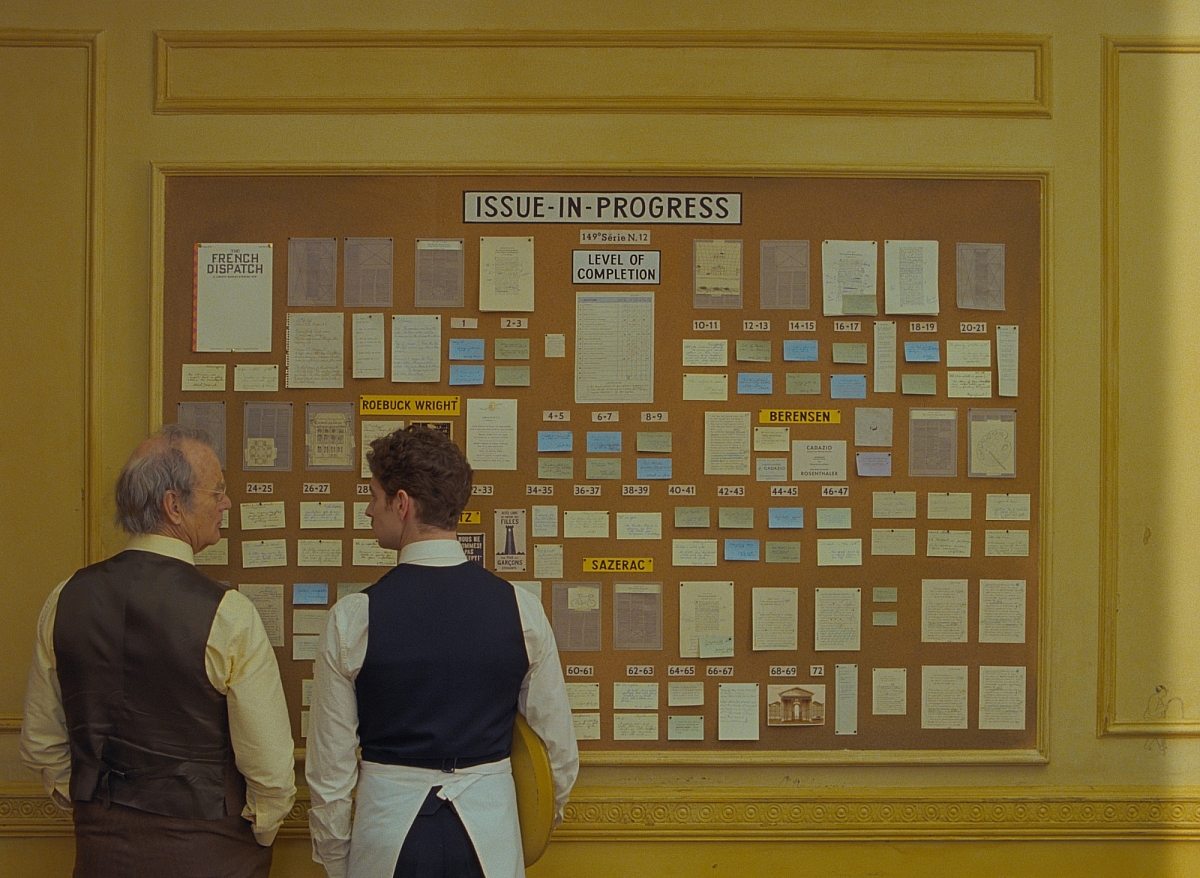

The film has been described as, "A love letter to journalists…in a fictional 20th-century French city.” Reported to be set after World War II, it concerns an American newspaper editor who runs a magazine in France and who regularly sends stories about various aspects of French life back to the United States. Typically, different personal stories are knitted into the fabric of the film.

The extensive ensemble cast brought together for The French Dispatch, comprises some of Anderson’s regular favorites, such as Bill Murray, Frances McDormand and Tilda Swinton, plus supporting players from the director’s acclaimed The Grand Budapest Hotel, including Saoirse Ronan, Willem Dafoe, Mathieu Amalric and Adrien Brody. Actors Timothée Chalamet, Benicio del Toro and Elisabeth Moss make their debuts for the director, and other performers set to appear include Christoph Waltz, Lois Smith, Henry Winkler, Rupert Friend, Griffin Dune, together with the French actors Denis Ménochet, Guillaume Gallienne, Félix Moati and Vincent Macaigne.

Out of Anderson’s many creative collaborators, Yeoman is perhaps the most pivotal of all in helping to put the director’s cinematic vision on to the big screen. Apart from Anderson’s stop-motion features Fantastic Mr. Fox and Isle of Dogs, Yeoman has served as the cinematographer on every one of Anderson’s other productions.

(From L-R): Tilda Swinton, Lois Smith, Adrien Brody, Henry Winkler and Bob Balaban in the film "THE FRENCH DISPATCH." Photo Courtesy of Searchlight Pictures. © 2020 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation. All Rights Reserved.

The French Dispatch represents Yeoman’s eighth movie collaboration with Anderson, starting with his debut Bottlerocket (1996), followed by Rushmore (1998), The Royal Tenenbaums (2001), The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou (2004), The Darjeeling Limited (2007), Moonrise Kingdom (2012) and The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014). All were shot on 35mm film except Moonrise Kingdom, which harnessed 16mm.

Filming on The French Dispatch took place over the course of 50 days, around the picturesque city of Angoulême in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region of southwestern France, using practical locations that were carefully dressed to help depict the post-war time period. A variety of sets were constructed in a vacant factory, which was used for the production’s stage work.

“I first read the script of The French Dispatch in the summer of 2018,” recalls Yeoman, who earned a Best Cinematography Oscar nomination for his work on The Grand Budapest Hotel. “As usual I loved what Wes had written, although I knew that it would be a challenging shoot. But that is always the case with him. Many times he will describe the kind of shot he is looking for, and I’ll think to myself, ‘How am I going to do that?’ or ‘That's impossible!' It’s a big part of working with him, but we always find a way of pulling it off.”

Yeoman adds, “So much depends on our locations, so I try not to have too many preconceptions until I see them in person. When I arrived in Angoulême we spent a fair amount of time together looking at locations. We would sometimes take a film camera and shoot them in available light to get ideas. Often these tests were shot in extremely low light, and I was frequently surprised by how much detail the lab was able to bring out in the shadows. The latitude of film is extraordinary. From watching these tests, I was encouraged, when we came to shoot, to be more bold in the lighting and worry less about fill light than I have in the past.”

Timothée Chalamet and Lyna Khoudri in the film "THE FRENCH DISPATCH." Photo Courtesy of Searchlight Pictures. © 2021 20th Century Studios. All Rights Reserved.

Recalling the visual references for the film, Yeoman remarks, “Wes always supplies a library of DVDs, photos and books that the actors and crew can borrow to inspire them. He is a great fan and student of French filmmaking, especially the French New Wave and black and white photography.”

Among the many movies considered were: Le Feu Follet (1963, dir. Louis Malle, DP Ghislain Cloquet), Classe Tous Risques (1960, dir. Claude Sautet, DP Ghislain Cloquet), Pépé Le Moko (1937, dir. Julien Duvivier, DPs Marc Fossard/Jules Kruger), Quai Des Orfèvres (1947, dir. Henri-Georges Clouzot, DP Armand Thirard), Vivre Sa Vie (1962, dir. Jean-Luc Godard, DP Raoul Coutard) and Touchez Pas Au Grisbi (1954, dir. Jacques Becker, DP Pierre Montazel).

“I personally brought my copy of In Cold Blood (1967, dir. Richard Brooks, DP Conrad Hall ASC) to the reckoning,” Yeoman declares. “One of our stories had some scenes in a prison and I drew from Conrad Hall’s daring lighting and B&W photography as inspiration.”

Yeoman shot The French Dispatch with ARRICAM ST and LT cameras, fitted with Cooke S4 prime lenses, supplemented with an occasional zoom, framing most of the action in Academy 1.37:1 aspect ratio.

Bill Murray and Pablo Pauly in the film "THE FRENCH DISPATCH." Photo Courtesy of Searchlight Pictures. © 2020 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation. All Rights Reserved.

“We previously shot this way on The Grand Budapest Hotel, as 1.37:1 helped to delineate the 1930’s period of that film. Both of us also loved the possibilities for compositions, and were very happy with the results,” Yeoman explains. “This aspect ratio was also used in many of the French films that inspired us and, similarly, it helped enhance the feeling of the time we wanted to evoke on The French Dispatch. Occasionally, we shot a scene in Anamorphic, mainly to make a bold dramatic statement.” The camera and lens package was supplied by RVZ in Paris.

With the director and DP both being celluloid stalwarts, there was never any film vs. digital debate. Yeoman, who always operates the camera on Anderson’s movies, shot The French Dispatch on 35mm celluloid, utilizing KODAK VISION3 200T Color Negative Film 5213 for the movie’s color sequences and EASTMAN DOUBLE-X Negative Film 5222 for the B&W sequences. Both stocks were used for interior/exterior and day /night scenes. Yeoman rated the 5213 at 200ASA and shot daylight without an 85 filter. The 35mm rushes were processed normally, without any push or pull processing, at film lab Hiventy in Paris, with Sixteen/19 delivering the dailies.

Photo by Roger Do Minh. Courtesy of Searchlight Pictures. © 2021 20th Century Studios. All Rights Reserved.

“I like the aesthetic feel of celluloid, and the texture of film grain was an important element in the look of this film, particularly from the B&W stock,” says Yeoman. “Originally we planned to shoot less of the movie in B&W, but we both fell in love with the KODAK DOUBLE-X Negative look and shot more scenes with it than were originally intended. In the end the movie is about one half in color and one half in B&W.

“We have a small crew on-set, and no video villages. The only screen is a small handheld monitor that Wes holds as he sits next to the camera. Generally, he watches the actors and occasionally glances at the monitor to see how the shot is working. There is ordinarily no playback, unless there is some type of stunt or effect, and not a lot of discussion. The fewer people on-set, the happier he is.”

Stephen Park in the film "THE FRENCH DISPATCH." Photo Courtesy of Searchlight Pictures. © 2020 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation. All Rights Reserved.

Speaking about his approach to motivating the camera for storytelling purposes, Yeoman observes, “As always, Wes pushed all departments to think outside the box and come up with more creative ways achieve what he has imagined. He prefers using simple, imaginative rigs than modern equipment to achieve our shots. It is not always easy but the results are always rewarding.

“The French Dispatch was carefully planned out before we shot, and Wes was very specific about his camera moves. Our grip equipment was fairly standard except for some very intricate dolly moves that Wes had designed, which meant we brought-in a lot of track. At times we had a track on top of a track so we could move both laterally and in and out within the same shot. We generally shot all of the moves on the dolly on tracks. There is one sequence that was filmed entirely handheld, and only one Steadicam shot, as Wes is generally not a Steadicam person. His shots are so exact that it is difficult to achieve them with a Steadicam. For very high angles we were typically on a scaffold, as opposed to a Technocrane, as he prefers the older style of executing shots.”

Yeoman’s lighting package, provided by Transpalux in Paris, included a bevvy of HMIs, Tungsten lights, ARRI Sky Panels, plus other smaller LEDs, all depending on what the scene and location called for.

“Wes and I thoroughly discussed our lighting approach to each and every scene,” Yeoman explains. “I know his preferences and would try to give him options wherever I could. I also design the lighting so we can move quickly while shooting and not take much time between set-ups.

(From L-R): Elisabeth Moss, Owen Wilson, Tilda Swinton, Fisher Stevens and Griffin Dunne in the film "THE FRENCH DISPATCH." Photo Courtesy of Searchlight Pictures. © 2020 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation. All Rights Reserved.

“As always we used the French New Wave as our inspiration. We hoped for cloudy days and the sky was generally cooperative, which meant we rarely used lights on day exteriors. There were certain shots on the stage that required a stop of F11 to hold focus for the actors in both the foreground and background. So we bounced several 18Ks onto the ceiling (which was covered with white cloth), and hung some light grid underneath to further soften the lights. We used a lot of lights, but got our F11 on the Kodak 200T stock. We also used conventional Tungsten lights on night exteriors and during stage work. We particularly liked the Sky Panels for the amazing flexibility they give in terms of exposure and color temperature and used them extensively. Generally the light panels and Tungsten lights were programmed into an iPad so we could make adjustments and lighting changes within a shot very quickly.”

Yeoman’s crew included gaffer Greg Fromentin, who brought his lighting crew from Paris for the production. “We had a wonderful collaboration, and it was a pleasure working with someone who always had some suggestions about how best to light a scene and we worked together beautifully. Greg and his crew often anticipated our lighting needs and were one step ahead of me,” he says.

Photo by Roger Do Minh. Courtesy of Searchlight Pictures. © 2021 20th Century Studios. All Rights Reserved.

The 1st AC was Vincent Scotet, who Yeoman says was able to quickly adapt to his and Anderson’s unorthodox way of shooting. “He did an amazing job on focus. We often had to do splits to keep actors in different areas in focus and he was exceptional.”

Sanjay Sami, a regular with Anderson and Yeoman, performed duties as key grip. “Sanjay is from India and brings a wealth of experience from having worked all over the world. Wes would often describe a potential shot, and Sanjay always came up with the best solution to achieve it. At times his rigs were somewhat unusual but they always worked to perfection. His smile and sense of humour were always appreciated on the set and he even converted me into a Rugby fan!”

Yeoman concludes, “I just love the look of film, and we were all surprised by how much we liked the look of the B&W footage we had shot. This was something I don’t think could be achieved had we shot digitally.”