Kodak 16mm provides a privileged perspective for 2018 Cannes screener "Chuva É Cantoria Na Aldeia Dos Mortos" ("The Dead and The Others")

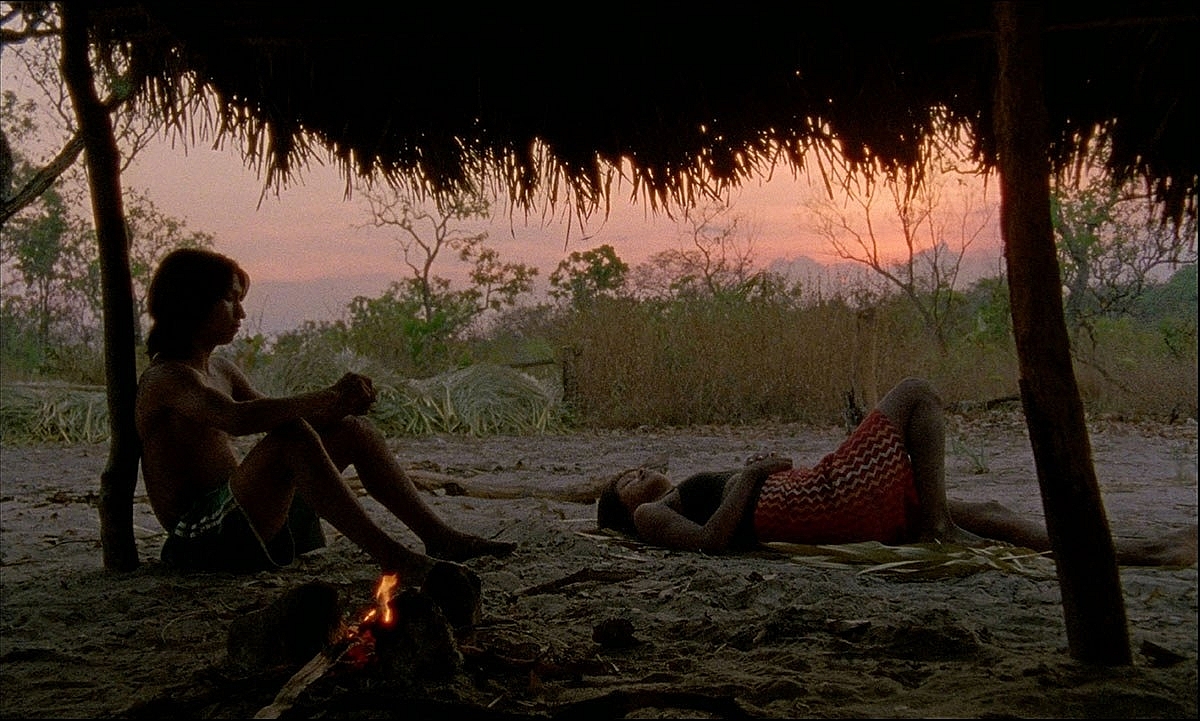

A still from 'Chuva É Cantoria Na Aldeia Dos Mortos' ('The Dead And The Others'), shot on Kodak S16mm by João Salaviza and Renée Nader Messora.

Shot in Super 16mm format using only KODAK VISION3 500T Color Negative Film (7219), the long-form narrative feature Chuva É Cantoria Na Aldeia Dos Mortos (The Dead And The Others), screening in the Un Certain Regard section of the 2018 Cannes Film Festival, provides a privileged perspective of the profoundly spiritual and deeply vulnerable indigenous Krahô society in northern Brazil.

Co-helmed by the multiple award-winning Portuguese director João Salaviza and Brazilian cinematographer Renée Nader Messora, the documentary-style production saw the pair travel to Pedra Branca, a small village in the protected Kraolândia Reservation, part of the remote state of Tocantins, some 1,000km north of the Brazilian capital.

Armed with a diminutive lens and camera package, no lighting equipment, and 85 x 112m rolls of 500T, they shot their touching, contemporary story in chronological order over a nine-month period, from June 2016 to February 2017, in searing heat and torrential seasonal downpours, with locals acting out the story from a loose narrative structure in their native Krahô language.

Behind the scenes on 'Chuva É Cantoria Na Aldeia Dos Mortos' ('The Dead And The Others'), shot on Kodak S16mm by João Salaviza and Renée Nader Messora. Photos by Isabella Nader.

“Before we went, people said we were crazy and that what we wanted to achieve was impossible,” says Salaviza. “But I would like to think that this film, shot in Super 16mm, will inspire others to tell unique and important stories and demonstrate that it is perfectly possible, and actually very sensible, to film on film no matter what the challenges might be.”

The story of Chuva É Cantoria Na Aldeia Dos Mortos follows sixteen-year-old Ihjãc, who has been having nightmares since his father died. One night, when the village is quiet, he hears a distant chant coming through the dense palm forest. Magically, his father’s voice calls him to a nearby waterfall, and Ihjãc realizes that it is time to organize the traditional funerary feast so that his father’s spirit can depart from a state of limbo and enter into the ethereal village of the dead.

A still from 'Chuva É Cantoria Na Aldeia Dos Mortos' ('The Dead And The Others'), shot on Kodak S16mm by João Salaviza and Renée Nader Messora.

Denying his duty, and in order to escape the ritual process of becoming a shaman, Ihjãc runs away to the city in search of broader answers. However, being far away from his people and his culture, he faces the harsh reality of what it is like to be an indigenous person in contemporary Brazil.

Brazilian cinematographer Nader Messora is no stranger to Kraolândia. She shot a short documentary about its indigenous people in 2009 and subsequently travelled back to the region on many occasions, encouraging the people there to record and register their remarkable traditions and rituals through cinematographic means.

A still from 'Chuva É Cantoria Na Aldeia Dos Mortos' ('The Dead And The Others'), shot on Kodak S16mm by João Salaviza and Renée Nader Messora.

“I was amazed with what I discovered when I first went there – the people and their way of life. And I started thinking of ways in which I could return there and tell the story of their remarkable community,” she says. “The idea for the story for Chuva É Cantoria Na Aldeia Dos Mortos came in 2014, when João and I were there on a parallel project with young cinematographers. We met a young man with a wife and young baby, who was questioning his way of life, his spirituality and his shamanism, and who ran away to the city in the hope of finding answers. But life in the city is extremely difficult for indigenous people, and it was very moving for us to witness this happening for real.”

Salaviza has shot all his productions on film. These include the 35mm short Arena, which won the Palme d'Or for Best Short Film in 2009; the 16mm-originated Rafa, winner of the Golden Bear at the Berlin International Film Festival in 2012; and the 35mm Montanha which, amongt many other accolades, garnered the Best Cinematography Award at the Manaki Brothers International Cinematographers' Film Festival in 2015.

A still from 'Chuva É Cantoria Na Aldeia Dos Mortos' ('The Dead And The Others'), shot on Kodak S16mm by João Salaviza and Renée Nader Messora.

“Renée and I always wanted to shoot Chuva É Cantoria Na Aldeia Dos Mortos on film, rather then digital,” Salaviza says. “We believed that only film could capture the reality of life in Kraolândia in a way that digital never could. Digital makes an interpretation of reality, and we did not want that to interfere with the reality of this production. By contrast, there’s something organic about film. The silver elements in the emulsion respond to the light on a mountain or the landscape of a face lit by flame, and the alchemy of the process connects you directly to the environment. Film negative does not impose itself on reality. Instead it absorbs reality and dances with it. It’s simple, natural and real.”

With their minds focused on both practicality and the need to pack light, the shooting kit for the production comprised of two Aaton 16mm XTR Prod bodies, plus a small clutch of vintage, but fast, Zeiss T.13 lenses and a Canon T2.5 zoom. In case of any mishaps or breakages, Nader Messora decided to shoot the 500T uncorrected, only using Neutral Density (ND) filters to mitigate the harsh daytime sunlight.

A still from 'Chuva É Cantoria Na Aldeia Dos Mortos' ('The Dead And The Others'), shot on Kodak S16mm by João Salaviza and Renée Nader Messora.

While the pair variously directed during production, Nader Messora operated the camera in an observational documentary style, while Salaviza took charge of the sound recording. The duo had no official crew and were grateful for the help of a small number of local people, who assisted with transporting the equipment between locations and positioning reflectors during takes.

“We were shooting quite a bit of handheld, including from the back of a motorbike, so I needed a light and maneuverable camera,” says Nader Messora. “In this respect the Aaton XTR Prod was perfect as it is compact, low-weight, quiet and was the only camera we could find that had an on-board battery. It also features a super sharp viewfinder, which I knew would be helpful for night scenes and daytime shots with strong NDs.”

A still from 'Chuva É Cantoria Na Aldeia Dos Mortos' ('The Dead And The Others'), shot on Kodak S16mm by João Salaviza and Renée Nader Messora.

Nader Messora selected the KODAK VISION3 500T Color Negative Film 5219 for the shoot as it would cover all bases. “We bought and transported all the stock we needed, as the Krahô village is so remote and complicated to get to,” she says. “We had no lights, just portable reflectors, and shot everything in natural or available light – such as fire light. Depending on the light during the daytime, I shot with different strengths of ND filters - normally a 6 or a 9. And the 500T faithfully captured the changes of the vegetation during our time – there from arid, golden browns in June, to luscious greens with hints of cyan in February – and the results are just amazing.

A still from 'Chuva É Cantoria Na Aldeia Dos Mortos' ('The Dead And The Others'), shot on Kodak S16mm by João Salaviza and Renée Nader Messora.

“But the 500T also responds beautifully in the dark. The images have impressive density, with deep, deep blacks. It is simply astounding way that 500T articulates the chromatic variations of flames in a soft breeze, and how it captures the quality of that light on skin, with soft grain. The results are rich, colorful and engaging.”

While Salaviza and Nader Messora are pleased with the outcome of their intrepid achievements, they are also eager to encourage others to shoot on film.

“We are not against digital, but we believe filmmakers must have the choice and option to use film,” says Salaviza. “Every year a new digital camera or binary format comes along, and we’re told that we have reached the top of the mountain, the pinnacle of image quality. But here lies a big problem: rolling obsolescence. If you look back at productions from 10 or 15 years ago, shot on the digital formats that were supposed to be at top then, they look out-of-date today. They were kidnapped by their own format.

“However, if you look at a feature shot on Kodak [film] over many decades, it’s still the same. The look of film is timeless, and you can really connect with that – which is vital on a story about real human relationships. No one can tell me things are impossible. When people see our film and understand our positive experiences, I hope it makes them think again and fight for film too.”