Kodak 35mm 2-perf film and experiential sound design bring a special resonance to director Darius Mauder’s must-watch movie 'The Sound of Metal'

"The Sound of Metal". Image courtesy and copyright of Amazon Studios.

Applauded as “intoxicating”, “imitate” and “unflinching”, director Darius Mauder’s debut feature, The Sound of Metal, shot in 2-perf on Kodak 35mm film, is one of the must-watch films of 2020. After playing in selected cinemas in the US, and releasing on Amazon Prime on December 4, the five-star rated movie may well find a place in the 2021 awards season nominations too.

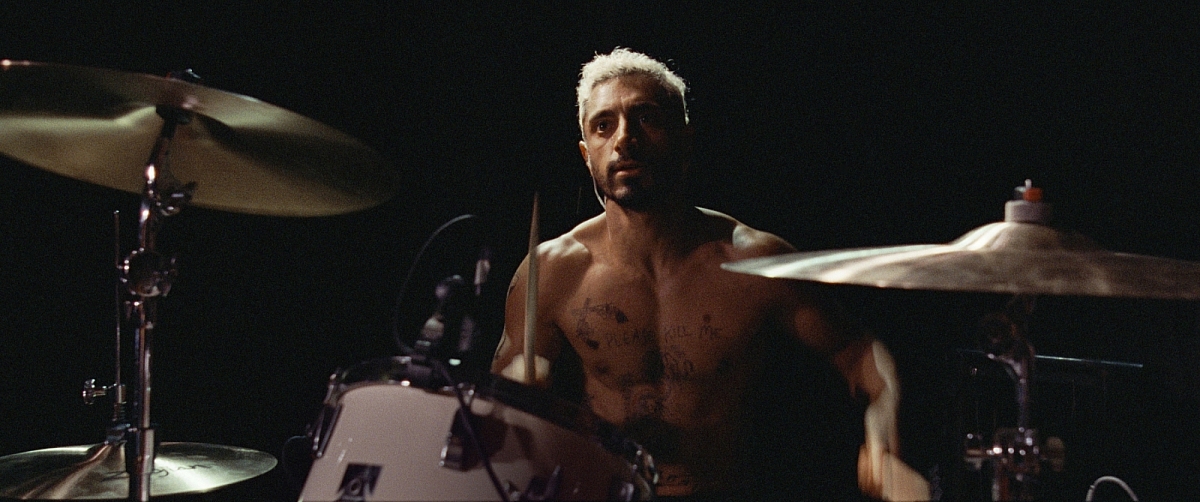

Directed by Marder (who also wrote The Place Beyond the Pines), and co-written with his brother Abraham, the film stars rising British actor Riz Ahmed as hard-rocking punk drummer, and recovering heroin addict, Ruben Stone. Living out of a ramshackle airstream RV, with his guitar-playing girlfriend Lou (Olivia Cooke), the pair perform together under the alias of ‘Backgammon’ and dream of making it big in the punk scene.

"The Sound of Metal". Image courtesy and copyright of Amazon Studios.

However, during a series of adrenaline-fueled one-night gigs, Ruben begins to experience intermittent hearing loss. When a specialist tells him his condition will rapidly worsen, he thinks his music career – and with it, his life – is over. Lou checks Ruben into a secluded sober house for the deaf, hoping it will prevent relapse into addiction and help Ruben adapt to his new situation. As he is welcomed into the community, Ruben has to choose between his equilibrium and the drive to reclaim the life he once knew.

Along with the emotionally-charged performances of Ahmed and Cooke, the critics have also noted the film’s mesmerizing cinematography by Dutch DP Daniël Bouquet NSC, combined with innovative experiential sound design techniques and the use of captions throughout the film to convey the effect of Ruben’s hearing loss.

"The Sound of Metal". Image courtesy and copyright of Amazon Studios.

Bouquet had around eight weeks of prep on the production before filming took place over the course of 24 non-consecutive shooting days at locations around Boston and Ipswich, Massachusetts, and also in Antwerp, Belgium, during the Spring, Summer and Fall of 2018.

“During my first call with Darius I expressed my desire to shoot The Sound of Metal on film, preferably in the fall or winter,” says Bouquet. “I could imagine that the character of 35mm in combination with the acoustics of the snow and the cold would suit this story well.

“Darius felt the same. The final picture needed a highly filmic look, a little gritty but saturated and rich at the same time, just like the music, and to offer a sense of documentary in terms of the space and freedom for the actors’ performances. Although shooting in winter didn’t happen in the end, we agreed on 2-perf 35mm because of the texture it would bring to the image and the framing possibilities of its widescreen format amongst all of the noise, the silent moments in the story.”

"The Sound of Metal". Image courtesy and copyright of Amazon Studios.

Early conversations about the film’s aesthetic revolved around a booklet of pictorial references, including photographs from Hedi Slimanes Diary and Eugene Richards 'The Blue Room,’ with the overall discussion focused on expressing emotions and communication, especially in a non-hearing context.

“Darius and I spoke about the perspective of ‘sound’. What does Ruben experience when he loses his hearing? What does the audience experience when he cannot hear? Does that need to be visible as well? That was an interesting conversation, especially together with sound designer Nicolas Becker,” says Bouquet.

“One film that was really inspirational to me in terms of smart, layered 35mm film photography was Wuthering Heights (2011, dir. by Andrea Arnold, DP Robbie Ryan BSC ISC), especially the scenes with the younger Heathcliff. They feel free and intuitive but are actually very well chosen and very specific. I found it beautiful how they showed time passing in the details of an insect on a cracked, drafty window. That's a very visual language and we felt that The Sound of Metal was going to have something similar on an auditory level as well, with the camerawork kept sincere, reserved and natural.”

Realizing he would need an affordable sync-sound camera configuration, which was also mobile enough to manoeuvre in the smaller spaces of the couple’s RV-cum-sound studio home, Bouquet went with the Aaton Penelope 35mm camera, plus Sigma lenses.

“I’m a big fan of the Aaton Penelope because it is very quiet in 2-perf mode, as well as being compact and very lightweight,” says the DP. “Even though they aren’t very costly, the Sigma lenses have been produced with many years of lens knowledge in the back pocket. I did a little test in Amsterdam and chose them because of their character, size, speed and ability to close focus.”

Bouquet selected a trio of KODAK VISION3 filmstocks for the production – namely, 50D 5203, 250D 5207 and 500T 5219.

“We had a dynamic schedule and preferred to spend our limited amount of production time on performance and to keep the overall look pretty natural,” explains Bouquet. “So I planned to use available light and to keep the lighting set ups minimal, which meant I had to be a little creative with the exposure sensitivity throughout the production.

"The Sound of Metal". Image courtesy and copyright of Amazon Studios.

“For the day exteriors the 50 ASA was more than enough, and the 250D gave me all the dynamic range I needed to capture the highlight and shadow details of the day interiors. I used the sensitive 500T Tungsten balanced stock for the night scenes. I did some push-processing tests with the 50D to see how it could create a matching character with the 250D, but in the end I preferred the look of the 50D with standard processing.”

The Aaton Penelope camera was sub-rented from a cinematographic friend, along with accessories, through Camtec in LA, with film processing done at FotoKem.

Recalling the shoot itself, Bouquet says, “Although we filmed a lot in available light, we sometimes used a combination of smaller HMI’s, Skypanels and LED tubes where we felt it was necessary and worked pretty much handheld or on sticks in most of scenes.

"The Sound of Metal". Image courtesy and copyright of Amazon Studios.

“As the length of film in the magazine is a finite resource, not being able to continue shooting endlessly, as you might with digital, has distinct advantages. On a film like this it results in a different focus on every level in the team and this meant we often only needed to shoot one or two takes.

“The energy on set when shooting film is different. The pace is different too, and the level of concentration is higher. All of this helped. Celluloid film also gives the depth, character and the color reproduction that is often missing in digital projects. It’s just not true that a good image is always sharp, clean and perfectly exposed.”

Given the intensity of what the sound was doing, Bouquet in large part kept the camera work unshowy – using wide shots for place, close-ups for character, often intentionally lingering on a shot and not cutting away, especially in moments of silence.

"The Sound of Metal". Image courtesy and copyright of Amazon Studios.

“This places you even more in the moment and creates something uncomfortable in a good way,” Bouquet explains. “Cutting away could release you from that moment as a hearing person. But something that was very important in our process, was that this film was almost as equal for the non-hearing among us. So that meant that when there was sign language, I had to show more of the person’s body to give information. Otherwise a non-hearing person would not understand what he or she was ‘saying’ or ‘communicating’. And to show a certain expression on someone’s face would require an extra close up for that. We spoke a lot about this. And I learned a lot from working with deaf actors.”

The production team had only one day to shoot both of the concert scenes in the movie, performed by Ahmed and Cooke.

"The Sound of Metal". Image courtesy and copyright of Amazon Studios.

“It was an incredible to experience and shoot the live performance – both picture and sound – on stage. We shot handheld, often physically close-up, with Riz drumming passionately and Olivia on the microphone, guitar and operating a sampler. That really gave these scenes a lot of character and intimacy. The lighting was inspired by what was already hanging there at the location – not too pretty and overall dark. It was a very contrasty set-up and I was surprised to see how much shadow and highlight detail I had to play with afterwards in the final grade. And, I was happy with how the 35mm film rendered all the strange glares and strobes that reacted beautifully on their skin."

Sharing his more general thoughts about shooting on celluloid film. Bouquet confides, ”I studied, graduated and shot my first projects on celluloid film. I personally have not enjoyed the digital revolution over the past 15 years – partly because it has involved working out how to make video look like film, and partly because my interest in shooting and photography have had nothing to do with the digital process.

"The Sound of Metal". Image courtesy and copyright of Amazon Studios.

“The main reasons for shooting digital have often been that the process needs to be cheaper, or that consumption has become faster. I feel it’s important that we keep an eye on the value of things and stay critical in every sense. The speed at which we produce, shoot and sell content can sometimes reach a frightening level of superficiality. It’s important that we keep producing things in ways that motivate people to think differently, and not just to consume.”