Director Jaime Rosales goes all out for 35mm film production and post on his powerful family drama 'Petra'

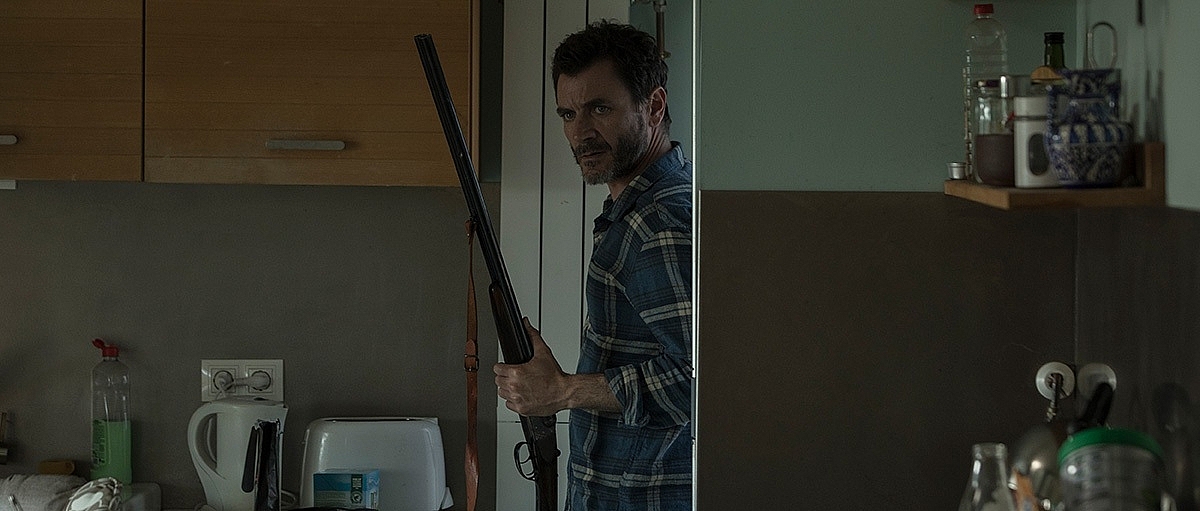

A still from director Jaime Rosales 35mm feature film "Petra." Image copyright and courtesy of Quim Vives.

Shot on Kodak 35mm film, Petra, directed by Jaime Rosales is screening in the Directors' Fortnight section at the 2018 Cannes Film Festival. While the powerful story, structured as a non-linear narrative, is sure to intrigue audiences, the tale of the production’s making is equally remarkable – involving one film camera, one lens, only Steadicam moves, and post-production completed on 35mm film.

The plot of Petra tackles the conflicts of a family who become caught up in a complex web of concealment, violence and resentment. The identity of Petra’s father has been hidden from her all her life. When her mother dies, she embarks on a quest, which leads to Jaume, a wealthy, celebrated artist and a powerful, ruthless man. As she searches for the truth, Petra meets Marisa, Jaume’s wife, and their son Lucas. Gradually the stories of these characters intertwine in a spirit of malice, family secrets and brutality. But fate’s cruel logic is derailed by a twist that opens a path to hope and redemption.

A still from director Jaime Rosales 35mm feature film "Petra." Image copyright and courtesy of Quim Vives.

Petra is the sixth feature to be shot on film by Rosales and stars Bárbara Lennie and Álex Brendemühl among the lead actors. The story was originated by Rosales, and the screenplay was co-written by Clara Roquet and director Michel Gaztambide.

The production filmed for 36 days during April and May 2017 in Spain, encompassing interior and exterior locations in Madrid and the northeastern countryside close to the Spanish/French border.

A still from director Jaime Rosales 35mm feature film "Petra." Image copyright and courtesy of Quim Vives.

“I have never shot digitally. It simply makes more sense to shoot on film,” says Rosales. “Cinema can be transcendent – it should be read by contemporary audiences but also kept for generations to come, so they can reflect on our time and our human condition. The best technical and artistic support for that is celluloid. It requires craftsmanship, it is beautiful to watch, and it is possible to preserve and store film a long, long way into the future.”

To bring the script to life on the big screen, Rosales called upon the cinematographic talents of French DP Hélène Louvart AFC. “Hélène and I are on the same aesthetic wavelength,” he says. “Her work is simple, realistic, beautiful and natural – not enhanced with artifice. It’s totally the type of cinematography I like. So there was not much need for us to talk about the final look of the film. More important was the camerawork and how the mise-en-scène would help to tell this story.”

DP Hélène Louvart AFC takes a meter reading during production on "Petra." Image copyright: Quim Vives.

One of Rosales’ chief objectives was to keep the characters in frame throughout the production, with the camera movement supporting the narrative timeline while also describing the emotions and feelings of the characters at any one moment. He also wanted to shoot long scenes with no cuts.

With this in mind, Louvart and Rosales synthesized a shooting praxis that involved framing the action on 35mm in 4-perf widescreen 2.39:1 aspect ratio, but using only one lens – a Cooke Anamorphic 50mm. They also decided to capture the entire film using just Steadicam.

Director Jaime Rosales and DP Hélène Louvart AFC eye-up a shot during production on "Petra." Image copyright: Quim Vives.

As Louvart explains: “You can frame with Anamorphic in many ways – it’s good for bold and emotional framing of one person at the center or the edge of screen. You can also compose the image and use the focus in different ways for a two shot or a group of actors. And it’s always good for landscapes. The Cooke 50mm Anamorphic has an engaging softness and, in combination with Kodak film, I knew it would be a good combination to balance the contrast on our sunny exterior shots.

A still from director Jaime Rosales 35mm feature film "Petra." Image copyright and courtesy of Quim Vives.

“However, bearing in mind that this story would not unfold in a chronological order, we realized that we had to be very careful as to what to give the audience visually. If we gave them too much they might see through the story, but if we didn’t give them enough they might find it too difficult to follow. So we had to find a stimulating equilibrium to retain the audience’s participation, and we felt that Steadicam provided the answer.”

A still from director Jaime Rosales 35mm feature film "Petra." Image copyright and courtesy of Quim Vives.

In practice, this meant the camera movement and framing had to be very smooth and precise, as Louvart explains. “As we were using just one lens, we had to physically move the camera back for a wide shot, or move in for a close-up. Some scenes might involve a reverse shot. So, as were doing just one long take, we spent a lot of time on the choreography of the camera around the characters, always being careful that it linked to the beats of the story but never revealing too much about the story. We never used a tripod or dolly, just the Steadicam, operated by Peke Griffin with the same ARRI LT camera and the same 50mm Anamorphic lens.”

DP Hélène Louvart AFC contemplates the light on an interior during production on "Petra." Image copyright: Quim Vives.

As for the film stocks, Louvart selected KODAK VISION3 250D Color Negative Film and VISION3 500T Color Negative Film 5219 for the production. “They are both not too contrasty, have good on skin tones, and match well together,” she remarks. “The 250D is excellent when you shoot outside – especially in the harsh Spanish sunshine. It’s very natural and faithfully captures what is in front of the camera, which is exactly what we wanted on this production.

A still from director Jaime Rosales 35mm feature film "Petra." Image copyright and courtesy of Quim Vives.

“The 500T is great for shooting interiors and nighttime sequences. It has the latitude to retain nuanced detail in the deepest of the shadow areas and treats highlights kindly in the same image. It offers versatile looks too. Depending on the scene I might shoot uncorrected for a slightly colder look or add different levels of correction to warm the image slightly, depending on the scene.”

The film negative was processed at Hiventy in Paris, with a modicum of pull-processing – from a half to one stop – on both stocks to mitigate the contrast of the sunny day exteriors or window-lit interiors.

Director Jaime Rosales and DP Hélène Louvart AFC muse over the interior lighting on "Petra." Image copyright: Quim Vives.

“What has always been good with film is that there is always an element of pleasant surprise when you see your rushes,” Louvart notes. “As much as you have to be alert and bring control to the exposure and lighting on set, you don't know exactly how the color, contrast, highlight, darkness will render. But film is kind, and it delivers an organic look, which I believe audiences will feel in this production.”

While Rosales prefers not only to shoot on 35mm, he likes to edit on film too, and Hiventy supported a full, 35mm, photochemical post production workflow on Petra. Once the takes from the rush prints had been selected, Rosales set about the process of neg-cutting, followed by color timing under Hiventy’s auspices, before making a final print on 35mm. It was only then that Rosales created a DCP of his film for screenings where a digital print is required. The DCP was created by colorist Jérôme Bigueur at Hiventy by eye-matching to the 35mm print.

DP Hélène Louvart AFC checks out the lighting, whilst director Jaime Rosales speaks to actor Alex Brendemühl shot during production on "Petra." Image copyright: Quim Vives.

“Funny enough, it is not more expensive to do a film post-production workflow. It’s just handled differently than digital. If you manage it they way I did, then it is perfectly affordable,” says the director.

While Rosales personally covets celluloid production, he is eager for other filmmakers to embrace film for the productions too.

The clapperboard for director Jamie Rosales’ 35mm film "Petra." Image copyright: Quim Vives

“When you make a movie, you need to create a dense image that transcends through time,” he says. “That density comes from the human content created by director, actors and crew, the mise-en-scène, and the capture medium of the image. By it’s nature, celluloid has more density than the digital image, and the image instantly becomes more valuable. I would encourage more directors to choose film. It is timeless.”