How Hoyte van Hoytema FSF NSC ASC pioneered with Kodak large format film for the supernatural sensation 'Nope'

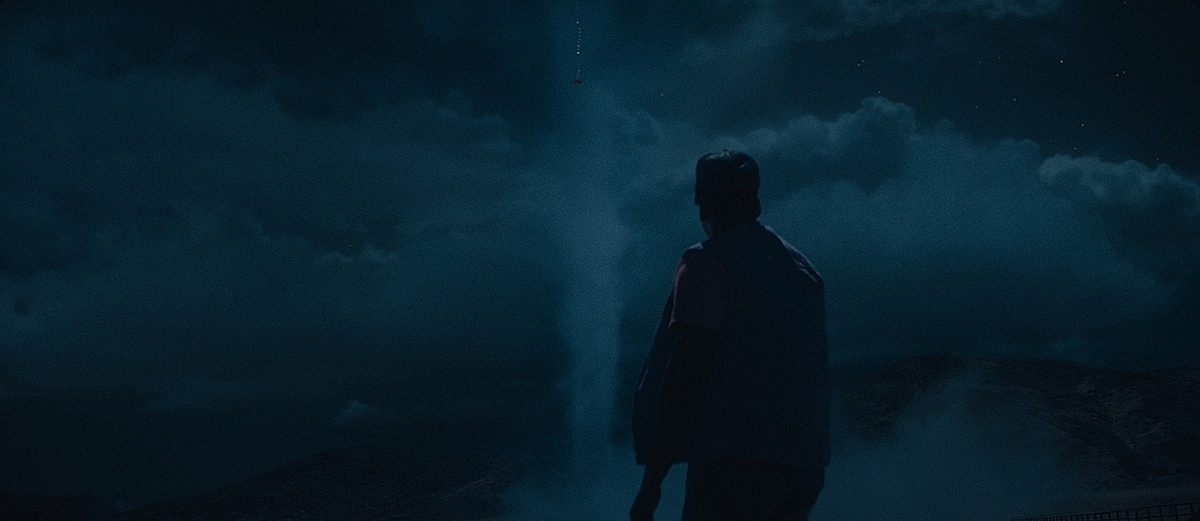

Daniel Kaluuya as OJ Haywood in "Nope," written, produced and directed by Jordan Peele. © 2022 Universal Studios. All Rights Reserved.

For his next and most ambitious film to date, the spine-tingling, supernatural Nope, filmmaker Jordan Peele told his cinematographer, Hoyte Van Hoytema NSC FSF ASC, that he wanted audiences to experience an event, "an immersion of awe and a fear and wonderment that we all had when we were kids."

And in response to this not inconsiderable challenge, Van Hoytema turned once again to film – large format IMAX (15perf) and 65mm (5-perf) Kodak celluloid – to deliver that otherworldly experience. The eminent DP had previously shot Dunkirk (2017) and Tenet (2020) for director Christopher Nolan using IMAX and 65mm large format film cameras, and says, "They’re my favorite mixture lately."

But Van Hoytema didn't stop there. In somewhat of a technical and creative masterstroke, he conjured up something quite bold and innovative when it came to the challenges of shooting the movie’s eerie nighttime sequences, which also bring new opportunities to other filmmakers.

To begin with, however, Nope represents the first collaboration between Van Hoytema and Peele, although the pair were highly aware of one another’s work. Peele has said, "The great Hoyte Van Hoytema is one of the best cinematographers and a mastermind behind some of my favorite films and favorite imagery, and this was a bigger adventure than I ever tried to tell, and by far my most ambitious."

DP Hoyte Van Hoytema NSC FSF ASC with writer/producer/director Jordan Peele on the set of "Nope." Photo by Glen Wilson/Universal Pictures. © 2022 Universal Studios. All Rights Reserved.

For his part, Van Hoytema, an alumnus of Łódź Film School in Poland and the visual author of films such as Let the Right One In (2008), Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (2011), Interstellar (2014), 007 Spectre (2015) and Ad Astra (2019), all of which were shot on film too, remarks, "I always wanted to work with Jordan, but for silly reasons this did not happen until Nope. We had a very good chemistry when we first met. It was very exciting for me, and it hasn't stopped being exciting ever since."

Starring Daniel Kaluuya, Keke Palmer, Steven Yeun and Michael Wincott, Nope follows the residents of an isolated town who witness a mysterious and abnormal event. After random objects fall from the sky, resulting in the death of their father, ranch-owning siblings OJ and Emerald Haywood attempt to capture video evidence of an unidentified flying object with the help of tech salesman Angel Torres and documentarian Antlers Holst.

Prior to the movie's global release, nothing else was known about the storyline of the hotly anticipated movie, but Van Hoytema was prepared to give wonderful insight into his work on the project and his radical initiatives.

"I find filming on film an extremely exciting and positive experience," he says. "What has been seen for years as some sort of a stubborn, nostalgic love for film amongst filmmakers is proving to be a very viable quest to deliver incredible cinematic experiences.

OJ Haywood (Daniel Kaluuya), Emerald Haywood (Keke Palmer) and Angel Torres (Brandon Perea) in "Nope," written, produced and directed by Jordan Peele. © 2022 Universal Studios. All Rights Reserved.

"When you shoot on 65mm 5-perf film, and watch it in a cinema, you witness something that you will see nowhere else. There's a quality and a depth to the image that is just unprecedented, and therefore so much more special. The moment you go to an even bigger format, like IMAX 15-perf film, the image depth and color depth are even more astounding to behold.

"It was very nice working with Jordan because he just wanted the best-of-the-best for a cinematic experience and was totally committed 100% to creating a spectacular event. So it was pretty much a no-brainer for us to end up at this combination of 65mm and IMAX film."

Nope has been described as a sci-fi horror, although this is not a label to which Van Hoytema readily subscribes.

"It's very difficult to pinpoint a genre when Jordan presents his script to you, and it was evident from the very first line of Nope that he had a specific intention and intellectual mindset about what he wanted to make, and how he wanted to make it, which seeped through every subsequent page," recalls Van Hoytema. "His script was more like entering a universe, and he was interested in making something supernatural with an air of incredible suspense. So, to call Nope a sci-fi horror really does not do it justice at all."

Behind-the-scenes photo from the production of Jordan Peele's "Nope." Photo by Glen Wilson/Universal Pictures. © 2022 Universal Studios. All Rights Reserved.

Van Hoytema says he and Peele checked out hundreds of images as reference points during prep on the movie, spit-balling ideas to arrive at a visual vocabulary for the film.

"However, when somebody is looking for something so specific and so unique as Jordan was for Nope, at some point we just sort of threw ourselves in the Jeep and started coming up with our own shit," he says. "Also, as a cinematographer you can easily gravitate towards what feels safe, so I constantly kick my own ass, question my motives and reassure myself that I am not choosing the path of least resistance in my photographic choices."

That said, Van Hoytema says he and Peele did watch a black and white print of King Kong (1933, dirs. Merian C. Cooper & Ernest B. Schoedsack, DPs Eddie Linden, Vernon Walker and J.O. Taylor) as, "Thematically, King Kong has a very similar story about aspiring human beings and was a remarkable spectacle when it first appeared."

Principal photography on Nope took place over 80 days, starting in June 2021, in a valley near Ague Dulce, northeast of Santa Clarita, California, where the family ranch and the elaborate Jupiter’s Claim theme park – a pivotal location in the narrative – were constructed to optimize the path of the sun and the geography of the storytelling. Other set builds were at Sunset Las Palmas Studios in Hollywood.

Behind-the-scenes photo from the production of Jordan Peele's "Nope." Photo by Glen Wilson/Universal Pictures. © 2022 Universal Studios. All Rights Reserved.

After the shoot, Jupiter's Claim was carefully dismantled and transported to Universal Studios Hollywood, where it was meticulously reconstructed and now resides as a permanent attraction between the Psycho and Jaws exhibits.

"Prep is a very important time for me in order to really consider what needs to be achieved and then to figure-out how to build any stuff that we’re going to need," says Van Hoytema.

"One of the major challenges on Nope was how we were going to shoot the night-time sequences, which were mainly all big set pieces. When Jordan and I went on the night scouts around Agua Dulce, we saw that there was no available light whatsoever, and realized there was no way we were ever going to be able to light and photograph these large expanses convincingly.

"But nature at night is very special and interesting. As we stood there, and our pupils dilated, we started to notice very fine details in the mountain ridges and the expansive presence of the space around us and thought it would be great to capture that essence in the film.

Daniel Kaluuya as OJ Haywood in "Nope," written, produced and directed by Jordan Peele. © 2022 Universal Studios. All Rights Reserved.

"Of course, we could have shot traditional day-for-night, but that has its limitations because you must have the sun exactly in the right place, or we could have tried greenscreen and CGI, but even then, the results can look kind of fakey."

Accordingly, Van Hoytema casted his mind back to some of his previous challenges and, with an inspired twist of creative thought, came up with a ground-breaking solution to shoot the night scenes and a pioneering new way of shooting day-for-night using a hybrid of film and digital.

As he explains, "When I worked on Ad Astra, we encountered a similar problem when it came to shooting the lunar battle/chase/action sequence with Moon Rovers in Death Valley, and our inability to light up a big area with a single light source. We needed to cover enough distance to be able to shoot the chase, but soft light or double shadows from any sources would have been an awful giveaway.

"So with the help of my friend, Kavon Elhami, who runs a camera house, we purchased two decommissioned 3D-stereo camera rigs on which we could mount two cameras. One was an ARRI Alexa, specially customized to capture infrared, the other a regular 35mm film camera. Instead of lining-up the cameras for 3D parallax, we found a new way to align them so that both cameras were shooting the exact same image – one infrared, the other on film – so that every frame would overlay perfectly later in postproduction.

A scene from "Nope," written, produced and directed by Jordan Peele. © 2022 Universal Studios. All Rights Reserved.

“The infrared camera is only sensitive to a very specific wavelengths of light and the images are monochromatic. When you shoot in natural sunlight, with a slight contrast boost, it results in images that are brightly lit, however, the skies are dark. The 35mm camera contains all of the vital color and texture information. In the perfect composite of the two images in post-production, the desert resembled the lunar surface. That meant we got close to the lighting character on the real moon.

“So for Nope, I had the idea of scaling up that same kind of rig and using it to shoot our day-for-night scenes in broad daylight – but this time using an ARRI Alexa 65, pointing upwards vertically and shooting in infrared mode, in perfect alignment with a Panavision System 65mm film camera, which was on the horizontal axis.

“However, it’s vitally important that the different gates and lenses are identical, that you have exactly the same depths-of-field, that your focus pulls translate in exactly the same way, and that the two images are completely in-sync.”

As part of his quest in creating the new day-for-night rig, Van Hoytema necessarily visited Panavison in LA, as the company owns and maintains the small number of existing 65mm cameras.

Writer/producer/director Jordan Peele at the camera on the set of "Nope," with DP Hoyte Van Hoytema NSC FSF ASC. Photo by Glen Wilson/Universal Pictures. © 2022 Universal Studios. All Rights Reserved.

"During the development and test phase we worked with Dan Sasaki, the magician at Panavision, who can build whatever you want, based on his understanding of physics and what is needed artistically," says Van Hoytema. "He made sure the twin sets of Panavision Sphero lenses we used were tuned to be identical in their performance."

Development of the specialist rig required a close cooperation between ARRI, Panavision, Van Hoytema and his own development company, Honeycomb Modular, in what he describes as "a beautiful collaboration between amazing people at amazing companies, to solve one person's obsession to do something a little weird and nerdy."

"In the early stages, we took a rather shabby-looking prototype rig, held together with screws, cable ties and gaffer tape, out into the desert to shoot tests. My DIT, Elhanan Matos, is not your standard DIT, and when we do new technology like this, he's all over it. He helped in getting the two-camera synched up, and although the video taps on the 65mm camera remain poor, he gave us a good on-set approximation of what the final image would look like.

"We then liaised with my DI colorist Greig Fisher at Company3 in LA, mixing those two sets of images together, and the result looked to me like an entirely plausible-looking night. In fact, using this technique you can peer much deeper into the dark expanse than we had done before on Ad Astra. And, after additional lighting effects were added in VFX, our night scenes really came alive. When you sit in the cinema, especially in an IMAX theatre, and you look around the image it’s a very, very special immersive experience."

Behind-the-scenes photo from Nope, courtesy of Hoyte Van Hoytema FSF NSC ASC. © 2022 Universal Studios. All Rights Reserved.

The production-ready day-for-night camera rig proved to be a sizeable, weighty and somewhat unbalanced lump, and it still needed to be motivated for visual storytelling purposes.

"We didn't want to be limited in terms of how we would move the rig around," says Van Hoytema. "So I worked with Dean Bailey and his team at Performance Filmworks, to work out how it could be adapted to fit on their various gyro-stabilized Edge cranes vehicles. I’ve worked with them before on Tenet and Dunkirk, where their vehicles had to drive over extremely rough terrain, and I had the same ambition to put this rig through equally rough stuff.

"They worked really hard to adapt their stabilized head for the rig, and all-of-a-sudden, we had the ability to drive everywhere – we could follow running horses and shoot other dramatic action scenes. It became a wonderful, crazy tool that was capable of giving us shot after shot that you might have thought were impossible and probably have never seen before."

As for the ramifications for other filmmakers, Van Hoytema says, "I think it's something that can, and probably will, be used more and more. Right now, through Honeycombe Modular, I am developing a new device that will enable you to use just one lens for two cameras, meaning that the rig can be much smaller, and any lens artefacts translate into both formats making post easier."

DP Hoyte Van Hoytema NSC FSF ASC operating the camera on the set of "Nope." Photo by Glen Wilson/Universal Pictures. © 2022 Universal Studios. All Rights Reserved.

Van Hoytema variously operated the IMAX and 65mm film cameras during what was mainly a single camera shoot, sometimes working on the shoulder, assisted by 1st AC Keith Davis pulling focus.

"I have operated these big cameras for several years now, and whilst they're heavy and lumpy, they are well-balanced. The shots are not long takes and operating with them is not quite as bad as people think. Keith has probably one of the hardest jobs on set, but we are like a well-oiled machine and he had it down.

"We tried to maintain all of the action pieces on IMAX film for the spectacle, and almost all of the two last acts were filmed on IMAX. But, of course, there's intimacy and dialogue in the film too, and on those occasions, we had to go with the System 65mm, as the IMAX cameras are noisy, like coffee grinders."

Operating duties were frequently shared with Kristen 'K2' Correll, who also operated B-camera. Key grip Kyle Carden headed the grip team, and the gaffer was Adam Chambers, whom Van Hoytema had at his side on Dunkirk, Ad Astra and Tenet.

Behind-the-scenes photo from the production of Jordan Peele's "Nope." Photo by Glen Wilson/Universal Pictures. © 2022 Universal Studios. All Rights Reserved.

Nope was shot principally on KODAK VISION3 250D Color Negative Film 5207 for the daytime, magic hour and day-for-night scenes, with KODAK VISION3 500T Color Negative Film 5219 used for some of the darker interiors and illuminated night scenes, plus KODAK VISION3 50D Color Negative Film 5203 for aerials. Film processing was done at Fotokem in LA, where 8K scans were down-rezzed to 4K for VFX and post-production purposes.

"I didn't do any push or pull processing, as we were shooting in the sweet spots on the 250D and 500T to deliver their beautiful depth of color and natural contrast ranges. Also the levels of their grain structures were exactly where I wanted them."

When it comes to lighting, Van Hoytema is all too aware of the new technologies, practices and roles abounding in that department.

"Working closely with Adam, my gaffer, we had Noah Shain as our lighting console programmer. He played a key role in overseeing the DMX networking and dimmer control of the lighting. Every lamp could be controlled individually, so we could adjust the illumination over large areas, or just specific fixtures anywhere around the sets. We could put a light source miles away and instantaneously control it. He even gave us control over the inflatable sky dancers spread across the huge fields that feature in the film.

DP Hoyte Van Hoytema NSC FSF ASC, with writer/producer/director Jordan Peele on the set of "Nope." Photo by Glen Wilson/Universal Pictures. © 2022 Universal Studios. All Rights Reserved

"Generally, I like my lighting package to have the nicest LEDs I can find and had the full range of ARRI Sky Panels at my disposal, as well as HMIs for pure power," he says. "But it's just absurd to me that, on a film set, you still have diesel generators churning out pollution. The environment is important to me, and the sooner we can move towards more sustainable, battery-driven sources of power, the better."

Van Hoytema concludes, "I admit to being extremely fanatic about film and like to keep pushing the boundaries. I had a wonderful time on this film, and would go out there and do it all again tomorrow morning, if somebody, especially Jordan, asked me to."