Monster Makeover

Article courtesy of British Cinematographer Magazine

Image courtesy of Chiabella James/©Universal Pictures

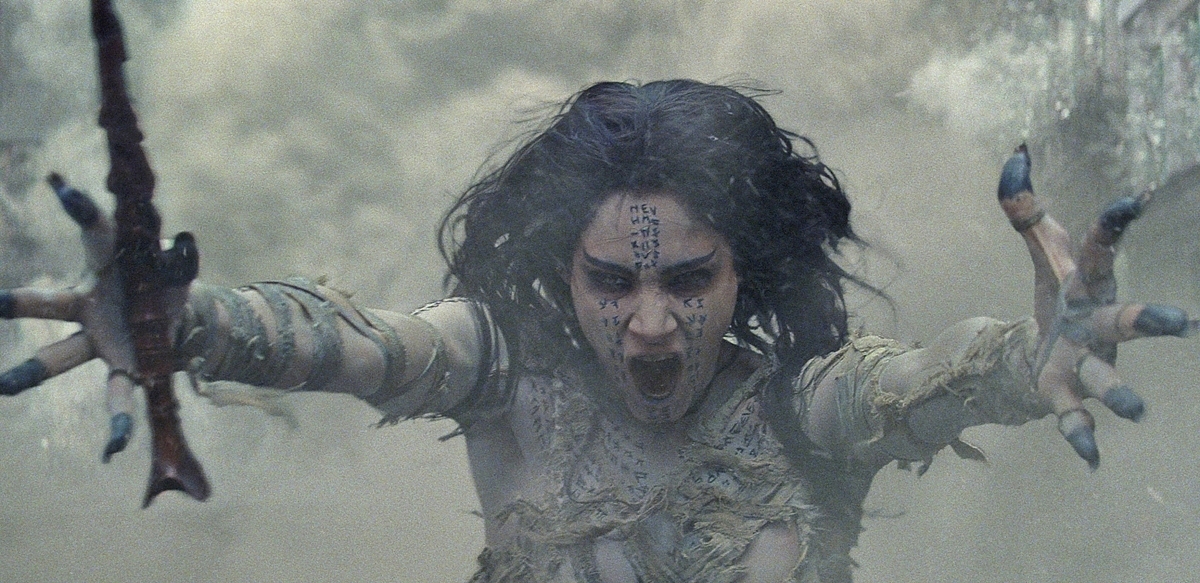

Once upon a time in ancient Egypt, a princess, named Ahmanet, was chosen as the new ruler. But her father did not wish to pass the throne to her, preferring a male heir. When she murdered him and attempted to claim the throne, her plan was thwarted and she was buried alive beneath the sands. When her tomb is rediscovered by the American Army in modern times, she is awakened, bringing with her a malevolent grudge and unimaginable powers that defy all humanity.

The tale of Ahmanet’s vengeful reappearance is told in The Mummy, a reboot of The Mummy franchise and the first installment in an octet of movies in the Universal Monsters shared universe – which will also see the return of Frankenstein, Count Dracula, The Wolf Man, The Creature From The Black Lagoon, The Invisible Man, Van Helsing and The Bride Of Frankenstein.

Image courtesy of Chiabella James/©Universal Pictures

Scheduled for release in 2D, 3D and IMAX 3D, Universal Studios’ $200m production stars Tom Cruise, Sofia Boutella, Annabelle Wallis, Jake Johnson, Courtney B. Vance and Russell Crowe. Directed by Alex Kurtzman and written by Jon Spaihts and Christopher McQuarrie, The Mummy was lit by cinematographer Ben Seresin BSC ASC.

Principal photography on 35mm film began in April 2016, on a multitude of elaborate sets built at Shepperton Studios, plus locations in London and Oxford, before the production moved to Namibia for two weeks, where the Middle Eastern desert scenes were filmed. The film wrapped in early August.

Seresin is no stranger to big-budget, action-packed features with narrative credits including Michael Bay’s Transformers: Revenge Of The Fallen (2009) and Pain & Gain (2013), Tony Scott’s Unstoppable (2010) and Marc Forster’s World War Z (2013). Ron Prince caught up with the cinematographer at his home in Los Angeles, to discover more about his take on reanimating The Mummy for 21st century audiences.

Image courtesy of Chiabella James/©Universal Pictures

How did The Mummy come your way?

BS: I had worked with Alex before. We crossed paths on Transformers 2, when he was one of the writers. He later called me to tell me The Mummy was coming up, and we met in LA. Although he had written and produced a number of Hollywood tentpoles, this was his first big event movie as director. I was also impressed to learn that he had been tapped (along with screenwriter Chris Morgan) to develop Universal’s new franchise of monster movies.

What appealed to you about the project?

BS: I was excited when Alex explained to me that the new films were to be action-adventure based, with big name stars associated with each, and that they would be reimagined in present-day settings in order to reintroduce them to contemporary audiences. I liked the thought of working with a director who is also a writer – they tend to be people who have a wider grasp on the material. It was also hugely appealing to me that The Mummy would set a new look-and-feel for the franchise, although our star had yet to be confirmed. I am a huge fan of diversity, and the beauty of this production was that it would allow me to step into a different genre. I love variation and the challenge of creating varied styles on different movies.

Tell us more about your initial discussions regarding The Mummy?

BS: There have been several Mummy movies down the years, that had very specific approaches and heightened aesthetics, which tended to give them a slightly distanced feeling. The plan was to take this new version to a different place – for it to be more grounded, fresh and connected to the present day, with a suspenseful approach around an out-of-control mummy, that would make audiences feel genuinely fearful and threatened. Some of the earlier films were slanted towards humour, and whilst this contains a degree of mirth, it does not interfere with the integrity of the threat and the fear.

With The Mummy having a contemporary look, how come you shot on 35mm film, rather than digital?

BS: The plan to shoot on film came as a direct result of our thinking about how best to support the idea of this production being real, suspenseful, visceral and gritty. I am not averse to shooting digitally, but when I consider the format that will see your vision through with the most integrity – that best emulates what your eyes see – film has those qualities. There are plenty of digital cameras that can be treated to give a film-style look, but when it comes down to dynamic range, extreme under/over exposure and colour representation, film has an X-Factor that is very pleasing visually.

Personally, I also like the process of using film – you have to trust your eyes, your instincts, the lab technicians and the unknown. Magical things can happen between the exposure on-set and the dailies, which can take your vision to another place. The digital alternative, which enables you to monitor on-set and react immediately, is great technically, but it can lead to a democratisation of the image, a committee of the pieces, and sometimes that is not in the best interest of the production.

Image courtesy of Chiabella James/©Universal Pictures

There’s a further consideration about shooting on celluloid: it gives you a degree of separation from the technological aspects of filmmaking. Sometimes the technical excitement about pixel count can dominate the conversation and take away from what’s most important – creating the images.

In these ways film sets a high bar. Despite the evolution of so many new digital cameras, film has not just survived - it’s resurgent. That said, whilst The Mummy was film from the get-go for us, Alex and I had to work hard to convince the studio. The decision to shoot on film became much easier when our lead came on-board. It’s incredible what star power can do!

What references did you consider to determine the cinematographic look?

BS: We looked at suspense-based films, especially Hitchcock movies. His films were often set in relatively banal situations, and it was interesting to see how, through carefully-choreographed framing and considered editing, he gradually cranked-up the suspense and horror out of those ordinary, everyday settings. The build-up of the threat, fear and paranoia, especially in The Birds (1963, DP Robert Burks), was really interesting to us. Contemporary films in this genre often lose this by filling the screen with as much production as possible. One of the key takeaways for us was not seeing, or not being able to immediately identify, the threat.

Less directly linked, but equally important, my other big avenue of exploration was art. I spent time at The National Gallery, considering 17th and 18th century painters, such as Canaletto, Carracci, Gainsborough and Turner – not so much stylistically, but for their abilities to tell a story in a single image. Paintings can trigger your imagination, especially in terms of composition, and how things can be played out in frame. Modern films, with complex camera work and fast-paced editorial style, don’t necessarily move the story forwards in a desirable or successful manner. Storytelling can work with minimal trickiness. You can allow the mechanics of the choreography to unfold in frame rather than making the camera do the work.

How did this influence your choice of aspect ratio and lenses?

BS: A wider frame is always good for storytelling. So we chose to shoot 2.39:1 Anamorphic as you can compose landscapes, single and multiple characters, as well as using the negative space for dramatic effect. But you can also let the choreography evolve and play out in a scene without moving the camera, saving more dynamic moves for when they really need to be used.

Did you work to storyboards and previz?

BS: There were some storyboards, but no previz – which was quite liberating for me, but much more challenging for the VFX team. I’m not averse at all to storyboards or previz, in fact I’m a huge fan in how they can help you construct a scene. But I prefer to refine these on-set and not to get locked-in by them.

What was your choice of camera and lenses?

BS: I went with Panavision’s workhorse XL camera for the majority of the shoot, with C- and E-series Anamorphics. They have a terrific softness and an overall look that place you in a world that is not affected by artifice. The aesthetic quality of the images emulates your own vision, and I like that.

I was positively influenced by what Chivo (Emmanuel Lubezki AMC ASC) did with close-focus on The Revenant, albeit with spherical glass, and wanted to explore this with Anamorphics. Traditionally, one of the issues of close-focus with Anamorphic lenses is that they can be unflattering on faces. Long ago, Dan Sasaki at Panavision in LA developed a 65mm Anamorphic enabling close-focus with minimal distortion and beautiful roll-off, and this is normally the go-to lens. I asked him to do the same on my 40mm and 50mm lenses, to adjust the focus down to a range of 20 to 22-inches. During production these became our go-to lenses, and I used them for 80% of the shoot. I also used some of the fantastic, T-series Anamorphics for longer-range shots. Although these are newer lenses, they have great colour and a visual quality that matches the C-series really well.

I did shoot a small number of shots digitally – the Alexa 65 for an underwater sequence, and the Alexa Mini for a sequence in the London Underground where it was really dark and we were limited to the amount of lighting we could take down. But the footage from both cameras fitted our look, and embedded well with the rest of the footage, which was all on film.

Which film stocks did you choose, and why?

BS: The Kodak Vision3 500T 5219 was my mainstay for the vast majority of the production on-set at Shepperton. It’s a fast stock that works incredibly well at the lower end of the exposure curve. The textural quality of the grain structure and the fall-off are just fabulous on deep under-exposures.

I used Kodak Vision3 200T 5213 on day exteriors and in available light during the Namibia shoots. Like the 500T, the 200T has lovely grain. Although the more usual choice is to go with the daylight stocks for day exteriors, I went with two Tungsten stocks for consistency of the recording medium.

The combination of the Anamorphics lenses with these stocks is very special. There’s an impressionistic flashback sequence early-on in the movie, featuring naked sirens, where the marriage of the light, lenses and celluloid made for a simply gorgeous result.

How long was your prep and what were your working hours during production?

BS: I had five months prep in total, the first two of these non-consecutive. It was good to come on-board early to start discussions with the production design and VFX teams about shaping the look and to then guide that process on an on-going basis. We shot for 110 days in total. My working regime during the first six weeks was full-on, seven days-a-week. Typically we would shoot for five days, rehearse on the sixth day, and pre-light up-coming sets and discuss any changes on the seventh. This was a huge production in terms of scale, and these sort of productions gain momentum as you get into the workload. It meant I didn’t see my children for a while, but I hope they’ll enjoy the movie when it releases.

Who were your crew?

BS: We shot mainly with two cameras, with a third ready as needed on the first unit, as well as for pick-ups and on the splinter unit. I had a great team: the maestro, Colin Anderson on A-camera and Steadicam, assisted by Pete Byrne; Graham Hall on B-camera, assisted by Kenny Groom; and Julian Morson on C-camera, assisted by Leigh Gold. We also had a very strong second unit led by Andrew Rowlands. They

are all huge talents in their own right, and I was very fortunate to have assembled such a strong team.

What was your thinking as regards the camera movement?

BS: Whilst The Mummy is action-packed, I am not a fan of moving the camera for the sake of it. We preferred to be judicious and move the camera when it felt right. So in high-energy scenes – such as the dramatic moments in the aircraft – we shot handheld, or we went with Steadicam. Otherwise, there were moments of tranquility when we preferred to let the performances play-out in front of the camera. I think this strategy allowed each to breathe.

Tell us about your lighting strategy?

BS: The theory was to keep the lighting real, atmospheric, and to steer clear from any form of heightened reality. On location we aimed to use natural light as much as possible, and to emulate that natural look on-set via the lighting plan.

Image courtesy of Chiabella James/©Universal Pictures

Early in the process, I investigated the use of arc lights, with enthusiastic support from the crew, and Tom. After a lot of research we found some functioning arc lights in Malta, Spain and the US, and managed to get half-a-dozen together. But we also needed the carbon arcs, and a separate worldwide search turned up a large batch in India, still used in cinemas there. After some tinkering to get a DC generator running we got a few arcs burning on-set, to much excitement. The quality of light is extraordinary, not replicated so far as a daylight source, and they are a great mix with film. We were on the home stretch. But one morning I awoke to a text message saying some blokes from Health & Safety had whisked them away, due to their asbestos linings. So our adventure came to an abrupt end, and bureaucracy won out. Fortunately, I had a large lighting package, from Pinewood MBS, of many ARRI SkyPanels and HMIs,standing-by to create the natural look we were after.

Image courtesy of Chiabella James/©Universal Pictures

The lighting on faces and close-ups was pretty conventional, keeping the look in the real world, nothing fantastic unless the setting called for something more elaborate. We used practicals as much as possible, although I kept these low-key.

During our time at Shepperton I actually had two gaffers – Jeff Murrell and Pat Sweeney – due to the fast pace of the production and the number of sets that Dom Watkins, the production designer, and his team were generating. Jeff worked with me on prepping and lighting sets in advance, and we would normally liaise at the weekends. Pat was with me as we shot. It was a great way to work, and meant the production was very efficient. When we wrapped on one set, the next was ready to go.

Image courtesy of Chiabella James/©Universal Pictures

Sometimes it can be a struggle to light at Shepperton, due to the restricted heights in the studios. I usually want to move the lights as far away as possible to get a better quality of light. However, the lighting for the Final Chamber, where the film’s finale takes place underground, was our biggest set by far. Despite the restrictions, it was exciting to light and shoot in, and I am really pleased with the results of that.

Where were the dailies processed?

BS: We processed the film stocks through Cinelab and i-Dailies (now Kodak Film Lab London), and I was very happy with their services. It is wonderful that London has a choice of labs.

Darren Rae at Pinewood Post managed the dailies. I watched 2K digital projected dailies every morning at Shepperton through a beautiful, brand new Christie projector. It was great to have this facility: when your pictures will eventually be displayed at 70ft, you must be able to do dailies review on a decent sized screen.

I kept reference stills of each day’s shoot in a look book, which I called The Bible. This was useful if we ever needed to revisit any sets or scenes, as well as being helpful in the dailies and later in the DI grade. I didn’t manipulate the dailies much as I wanted to keep the film as close as possible to what we shot on-set.

Where did you do the DI?

BS: I completed the DI with Stefan Sonnenfeld at Company 3 in Los Angeles. He’s terrific, a master of moods. He can find and augment the visual truth without extending the overall look too far from the one you want. I didn’t adjust the dailies much during production and the same was true during the DI. Again I used my Bible of looks, and we generally only made incremental adjustments in the DI, thereby pretty much retaining the on-set look in the final master.

What’s up next for you?

BS: I am looking out for more story-driven projects currently. But let’s see!