Kirill Mikhanovsky’s anarchic dark comedy 'Give Me Liberty' uses Super16mm for aesthetically spiritual sequences

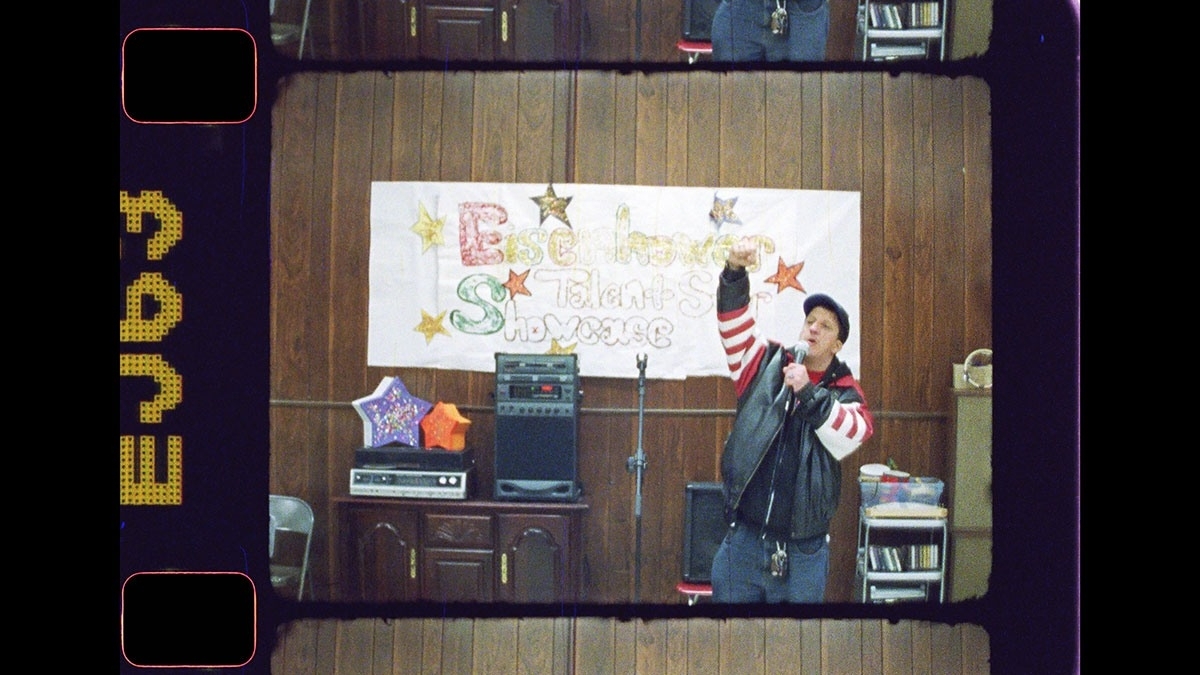

Aaron, an adult with severe neurological disabilities, singing at a talent show in Kirill Mikhanovsky’s anarchic dark comedy "Give Me Liberty"

Russian-born Kirill Mikhanovsky grew up in Moscow, where his early passion for cinema compelled him to skip school and go to the movie theatre across the street from his home where he watched countless films, often as the only person in the house.

After the Soviet Union collapsed, he immigrated to Milwaukee, where he had a series of odd jobs, including work as a medical transport driver for people with disabilities. He also began making films.

After graduating from NYU's Graduate Film Program at Tisch School of the Arts, Mikhanovsky went on to make films in the U.S., Brazil, Russia, and the Caribbean. A Sundance Artist Alumni, he shot his first feature Sonhos De Peixe (Fish Dreams) (2006, DP Andrij Parekh) on Super16mm and won the 2006 Critics Week Award at the Cannes Film Festival.

In 2019, the director made both the Sundance and Cannes festival headlines with Give Me Liberty – an anarchic cinematic portrait of marginalized communities, segregation, socioeconomic constraints and inter-generational conflicts. The buzz around the film was such that, immediately prior to its Cannes Director’s Fortnight debut, Music Box Films announced it had acquired the U.S. distribution rights for the movie, which was co-written with and produced by Alice Austen.

A hybrid production, mixing 16mm film with digital, shot by DP Wyatt Garfield, Give Me Liberty follows Vic (played by newcomer Chris Galust), a young Russian-American living in Milwaukee, as he endures a chaotic winter day on the job as a bus driver for people with disabilities.

Tracy (Lauren "Lolo" Spencer) as a young woman with severe ALS in Kirill Mikhanovsky’s anarchic dark comedy "Give Me Liberty"

Uproarious and freewheeling by turns, the film features moving performances and dark comedy from its cast of actors with disabilities. Vic's pick-ups include a morbidly obese man with an endless catalog of complaints and adults with severe neurological disabilities, one of whom is fixated on Elvis and is preparing to sing "Rock Around The Clock" at a talent show. Also among the passengers is Tracy (Lauren "Lolo" Spencer), a young woman with severe ALS from the African-American side of town, who inflames ugly tensions among the vehicle’s Russian occupants.

Almost every stop involves some fresh hiccup, and progress is slowed to a halt when police shooting-related protests cause several city blocks to be closed to traffic. Despite the protests, new connections are made, and unexpected acts of kindness occur, across cultural and racial divides.

Principal photography took place from mid-March to mid-April 2018, at locations across Milwaukee, including apartments and homes in the city’s Riverwest and Midtown neighborhoods.

“In terms of references, Kirill and I looked at a film called Voyages (1999, dir. Emmanuel Finkiel) that has very simple, honorable portraiture of Holocaust survivors, and also takes place on a bus,” says Garfield. “We looked at several Russian filmmakers too, both for their fearless and direct moving camerawork, and for their use of old Soviet filmstocks with muted palettes.

“Although we intended to shoot the entire movie on Super16mm, we ended up shooting digitally due to financial restraints, but did use KODAK VISION3 (7213) 200T 16mm to show the way Vic sees and remembers specific fleeting moments in the film.”

Vic (Chris Galust) the young Russian-American bus driver in Milwaukee Kirill Mikhanovsky’s anarchic dark comedy "Give Me Liberty"

Mikhanovsky adds, “The texture and the color rendition offered by film are sublime. The same thing shot on film and digital would be two different films. Film is fundamentally more humane.”

With the exception of the disco and the riot, lighting was almost largely practical and available natural light. “I like the restlessness of film, the way it reacts to bright light a bit unpredictably, and the way it softens and dithers detail. I also like how it makes people focus on what’s happening in front of the camera. With digital everyone obsesses over the flat image on the monitor, which can be very distracting,” says Garfield.

Give Me Liberty has been noted for the delirious whirlwind of Garfield’s vigorous and darting camerawork.

“We shot almost entirely handheld, sometimes propelling the camera on a custom rickshaw to get a wheelchair-bound feel,” he explains. “We wanted to keep the camera moving and maintain a kind of energy, and handheld provided us with the most flexibility to do this in the moving van. Scenes would often evolve spontaneously, and it was important to be able to adapt and not hinder the energy.

“They say the best camera is the one that’s with you, and this was true of Kirill’s personal Krasnogorsk,” he says. The Krasnogorsk-3 is a spring-wound 16mm mirror-reflex movie camera designed and manufactured in the USSR by KMZ. A total of 105,435 Krasnogorsk-3 cameras were produced between 1971 and 1993.

“The lightweight 'Kraz' was really nice for the fleeting quality of the images we were capturing. We also shot some choir performances on an ARRIFLEX SR-II 16mm donated from North American Camera.”

A choir performance in Kirill Mikhanovsky’s anarchic dark comedy "Give Me Liberty"

Garfield says production on the film was all about allowing chance into the process and letting it provide authenticity. “Many things were accidents, and not all of them happy! Kirill would build very specific emotion and energy with the cast, and it would often lead to remarkable, surprising results in front of the camera. So many things happened that we couldn’t predict: the woman doing a full split in front of camera at the disco was one of the funnier ones.”

On having used film as an important part of his production Mikhanovsky says, “I believe that cinema, the art of the 20th century, is film. As Wyatt pointed out correctly, film requires a more heightened sense of responsibility than ever before, more internal discipline, more preparation.

“With celluloid, I love the magic of not knowing exactly what we’ll see, as they are so very many variables – such as the chemicals, the temperature and speed of processing, etcetera. The world of film is metaphysical, and so is true Cinema. The benefits are aesthetic and spiritual.”