DP Charlotte Bruus Christensen opts for film on modern thriller 'The Girl On The Train'

Emily Blunt stars in DreamWorks Pictures’ The Girl on The Train credit: DreamWorks Pictures © DreamWorks Pictures

Danish cinematographer Charlotte Bruus Christensen DFF was determined that only 35mm film would suit the storytelling of Dreamworks’ psychological thriller The Girl On The Train.

Based on Paula Hawkins' 2015 successful debut novel of the same name, The Girl On The Train was directed by Tate Taylor, written by Erin Cressida Wilson, and produced by Jared LeBoff and Marc Platt. It stars Emily Blunt (Rachel), Rebecca Ferguson (Anna) and Haley Bennett (Megan), alongside Justin Theroux and Luke Evans, and follows an alcoholic divorcée who becomes entangled in a missing persons investigation that ultimately sends shockwaves through her life.

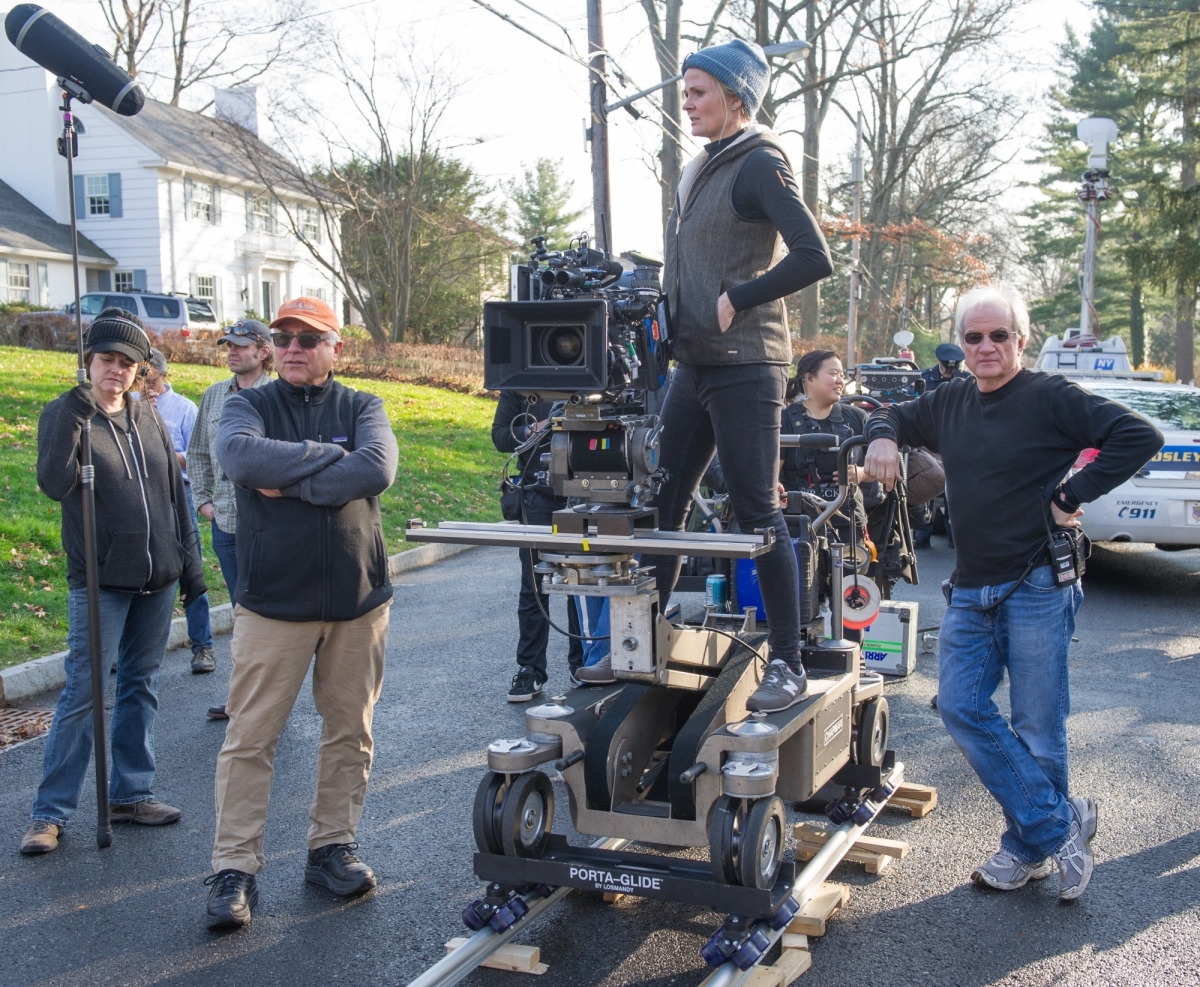

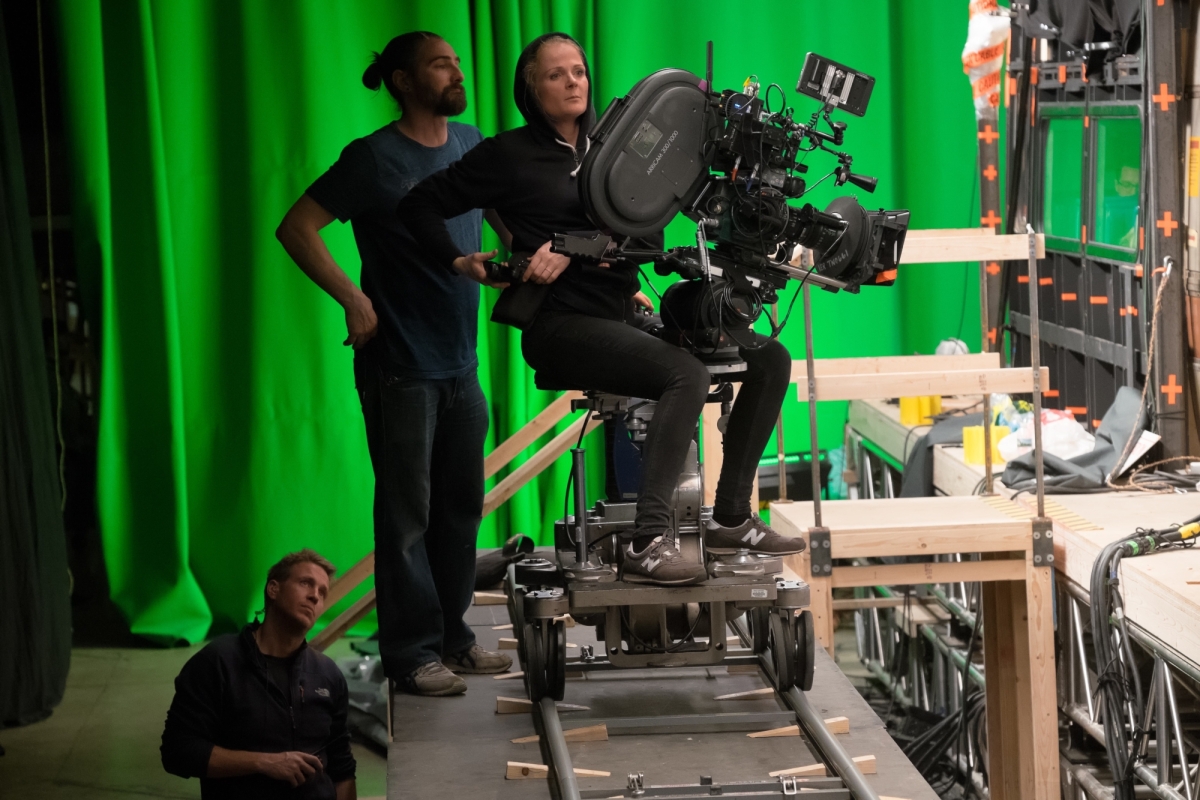

DP Charlotte Bruus Christensenin on set of DreamWorks Pictures’ The Girl on The Train Credit: 2016 STORYTELLER DISTRIBUTION CO., LLC

“Girl On The Train is not a pretty plot with beautiful backdrops – it’s real, rough and sometimes ugly – and the director and producers wanted an out-and-out contemporary thriller with a big visual impact,” declares Bruus Christensen. “With it being a modern, urban tale, based on a recent best-selling book, it seemed the immediate and obvious choice to shoot on video. But I had other thoughts, and I shared these openly with the director and the producers at the very start.”

Emily Blunt stars in DreamWorks Pictures’ The Girl on The Train credit: Barry Wetcher © DreamWorks Pictures

As she explains: “They wanted a point-of view movie, with the image close-up on the characters, especially Rachel, throughout the film. This would necessarily mean having the lens at very close proximity to the actors, sometimes within a foot of their faces. Emily is a natural beauty, but her look for this movie needed to be gaunt and careworn, with split lips, a drinker’s blotchy skin and a red nose. I knew that getting that look would require a lot of make-up. With video cinematography, the sharpness of the sensor would have resulted in an overly crisp and unforgiving image, resulting in a pretty big and time-consuming detour to fix-it in post-production.

“I reasoned that only film would render the images easily, and in a much more forgiving way. Celluloid has a cinematic purity that offers a straightforward opportunity to bring a texture to faces and feelings. Lighting happens from the lens and supports an honest visual language. This was an honest piece of filmmaking, and there was absolutely no point in shooting first and having the fight of manipulating the quality later, when you can automatically have the perfect starting point with film.”

Bruus Christensen framed the production in 1.85:1 aspect ratio, shooting with Arricam LT cameras fitted with Zeiss Master Prime lenses. “I like to light from the camera,” she says. “When I look through the eyepiece using a film camera, I know how the lighting is going to work. It’s far preferable than having to do in on a monitor or through an electronic viewfinder in the video world. I kept the lighting style very simple, mainly from one direction, to deliver simple but bold portraits of the characters.”

DP Charlotte Bruus Christensenin on set of DreamWorks Pictures’ The Girl on The Train Credit: 2016 STORYTELLER DISTRIBUTION CO., LLC

She selected a quartet of Kodak VISION3 filmstocks to suit the different atmospheric settings of the production, which took place during the winter months of 2015-16 at locations around New York city, White Plains and Hastings-on-Hudson.

“Whenever we had adequate light for daytime exteriors I used Kodak 5203 50D,” she says. “It’s simply a beautiful, straightforward stock that is true to the situation and the reality in front of the camera. It works well with the Kodak 5207 250D, which I used whenever the winter days were more overcast and also on certain day interiors.

Luke Evans as Scott in The Girl on The Train from Director Tate Taylor and DP Charlotte Bruus Christensen

“Kodak 5213 200T is also one of my favourites, as it’s very faithful in colour reproduction too. It proved perfect in supporting the different and dynamic interior palettes we wanted – such as the sombre green and blue of the fluorescent-lit train interiors, was well as the more homely colours of Rachel’s home, and the misty warmth of Anna’s house. Darkness plays a big part in this movie, and using Kodak 5219 500T for nighttime scenes allowed me to compose the frame with a lot of black in the image and amplify the suspense. Sometimes this was just down to the merest highlight in the actor’s eyes, so the audience can see directly into their soul.”

Bruus Christensen decided on a scheme of camera movements to suit the different situations of the female leads in the movie.

Emily Blunt stars in DreamWorks Pictures’ The Girl on The Train credit: Jessica Miglio © DreamWorks Pictures

“Rachel is drained and her world is uncertain,” she says. “She’s not sure what might be the truth or a deception, and has a compulsive preoccupation with the neighbors who she surveys from the train. To convey her state-of-mind, we used a lot of handheld camera with wide lenses. By contrast, the scenes involving Megan are much softer. She is running away from her past, and I felt the floating nature of Steadicam moves would be more appropriate for her situation. For Anna, who is caged-up indoors with a small baby, trapped in a miserable dilemma, I went for an immobile camera and static framing.”

Bruus Christensen says Girl On The Train was about special connections and relationships – between the cast and the crew, between the feelings and thoughts of the protagonists – and the key was all about shooting on film.

“Film is a portrait medium,” she exclaims. “It is naturally soft, balanced and cinematic – perfect for character-based movie scripts, like this, where the close-ups are of great importance. I fight for film and want more filmmakers to see why it is so worthwhile. Thankfully, Tate, Jared and Marc agreed with my approach, and I’m thrilled with the on-screen results. When I came to shoot my next movie, Fences with Denzel Washington, he was already on the same page about shooting on film.” But that’s another story.