Kodak 35mm film delivers a vivid and unsettling visual trip on 'Cordelia'

A scene from director Adrian Shergold’s feature "Cordelia." Copyright Cordelia/StudioPOW Limited.

Shot on Kodak 35mm film, Cordelia, directed by Adrian Shergold and executive produced by Oscar-nominated actress Sally Hawkins, focuses on the psychological trauma that comes back to haunt a young woman after she witnesses a shocking terrorist attack on the London Underground. An edge-of-the-seat thriller, the unnerving visuals for the production were realized on celluloid by British cinematographer Tony Slater Ling BSC.

Antonia Campbell-Hughes stars as the titular Cordelia, who lives with her twin sister, Caroline, in their late father’s dingy basement flat in a run-down part of London. Twelve years earlier, Cordelia, a promising actress, was caught up in the 7/7 London Bombings of 2005 that targeted commuters travelling on the city's public transport system during morning rush hour – an event that changed her outlook and emotional state. The fictional tale picks up on Cordelia’s story a decade later as her protracted return to stability and independence is placed into jeopardy. When Caroline and her boyfriend Matt set off for a weekend getaway, Cordelia becomes unable to manage on her own. She is left to cope with her mysterious neighbors, a haunting cello player and an eccentric old man, not to mention several house mice and a stalker. She quickly regresses back to the state of confusion she tried so hard to repress ever since surviving that terrible event so many years before.

Cordelia, which also stars Michael Gambon, Johnny Flynn and Catherine McCormack, was co-written by Shergold and Campbell-Hughes, and produced by Kevin Proctor of Studio POW. Kodak and Twickenham Studios were both production partners on the sub-£2M project.

DP Tony Slater Ling BSC shooting a scene on the London Underground on 35mm for director Adrian Shergold’s feature "Cordelia." Photo by Kerry Brown. Copyright Cordelia/StudioPOW Limited.

Principal photography, under Slater Ling’s supervision, took place over 26 shooting days, from May 16 to June 17, 2018. Interchangeable sets of both Cordelia’s and her neighbors’ flats were constructed at Twickenham Studios. Physical locations included Aldwych Tube Station, a subway at King’s Cross Station, and street exteriors in West Kensington in Central London, along with rural locations in Norfolk.

The film represents Slater Ling’s second feature film with Shergold, following their successful collaboration together on the highly-acclaimed Funny Cow (2017). The cinematographer had not shot long-form celluloid content since filming the Sky/LeftBank Pictures television series, Mad Dogs (2011), on 35mm, although he remains a fervent celluloid stills photographer and has also built his own mammoth plate photographic camera, measuring a colossal 40 x 40-inches.

Director Adrian Shergold with a reposed Antonia Campbell-Hughes (Cordelia) during production on "Cordelia." Photo by Kerry Brown. Copyright Cordelia/StudioPOW Limited.

“Adrian wanted to explore a weekend in Cordelia’s life, where everything starts to implode for her personally,” recalls Slater Ling regarding his early conversations about the production with Shergold.

“His script was quite abstract. Odd and strange events happen, and it is not always certain whether they are real or figments of Cordelia’s imagination. In a way this film was a study about mental health, where the challenge was to visualize what you see and don’t see in relation to Cordelia’s paranoia and hallucinations.”

Visual inspirations for the production came from a range of suitably strange and uncomfortably claustrophobic movies, including Roman Polanski’s Repulsion (1965, DP Gilbert Taylor BSC) and The Tenant (1976, DP Sven Nykvist), along with Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom (1960, DP Otto Heller BSC) and Joseph Losey’s The Servant (1963, DP Douglas Slocombe OBE BSC).

A scene from director Adrian Shergold’s feature "Cordelia." Copyright Cordelia/StudioPOW Limited.

“We agreed that the framing and compositions should be classical in nature, with the camera motivated to follow the actors as a presence in itself, keeping especially close to Cordelia,” he says. “The idea was to make the image feel unsettling, whilst also being very much in the moment. Most of the action took place on the constructed sets, and Adrian and I loved the idea of long takes where we follow Cordelia in continuous moves around the apartment, although this necessarily brought challenges for both lighting and grip.”

Slater Ling framed Cordelia in 2.40:1 widescreen aspect ratio, using Cooke Anamorphic lenses in combination with ARRICAM LT and ST cameras, supplied by ICE Films in London. He selected just one filmstock, KODAK VISION3 500T Color Negative Film 5219, shooting with correction filters.

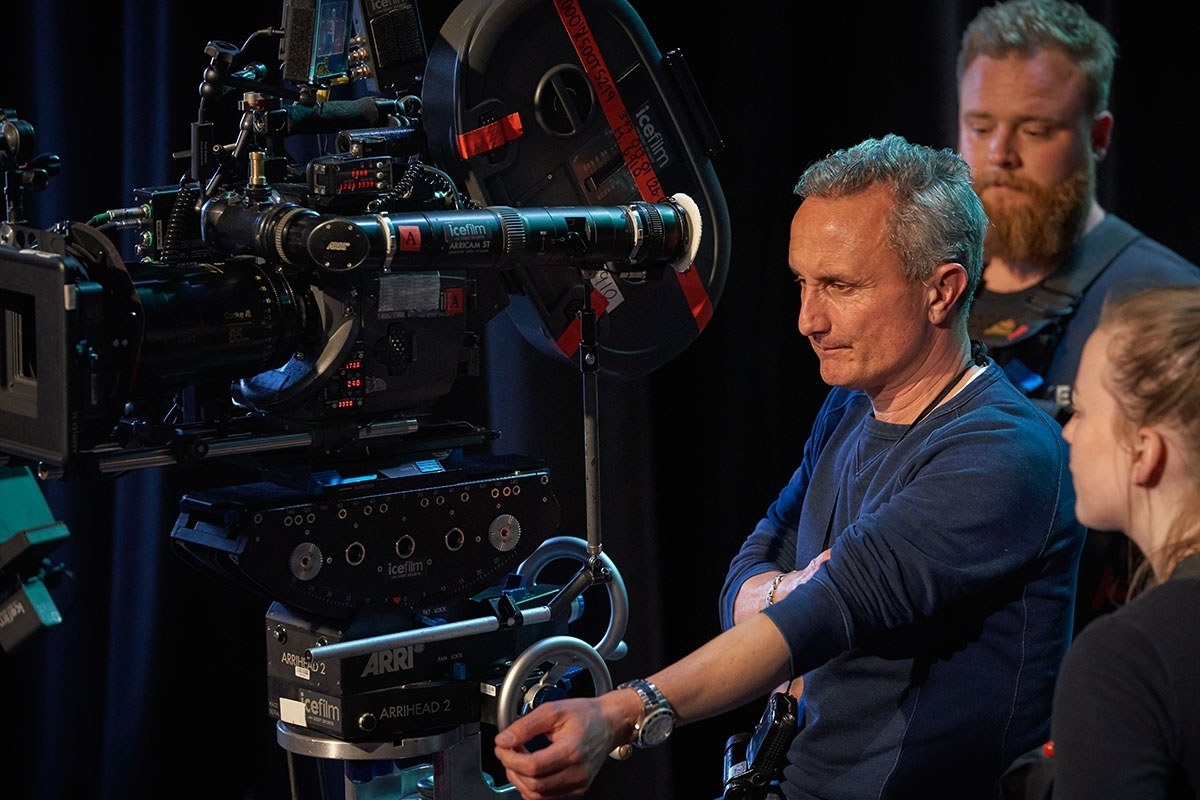

Director Adrian Shergold (l), producer by Kevin Proctor (m) and DP Tony Slater Ling BSC (r) at the 35mm film camera during production on "Cordelia." Photo by Kerry Brown. Copyright Cordelia/StudioPOW Limited.

“During pre-production Kevin, our producer, gave us the option of shooting on film or digital,” explains Slater Ling. “Adrian and I both loved the idea of shooting this story harnessing the texture and color capabilities of film, and Kodak were offering great incentives on 35mm filmstock, development and scanning costs. This allowed me to base the production around 35mm Anamorphic capture. For me, widescreen frames the face better with the benefit of also having ‘landscape’ in the background, and I kept close to Cordelia using the 40mm and a 65mm macro.

“I went with just the 500T as I knew I would always have adequate exposure and a universal consistency of textural grain in all of our day/night interior/exterior footage. I like my work to be imbued with a lot of color contrast, so we often had green/blue hues playing against yellow practicals and orange street lights in the same frame, all of which the 500T takes in its stride. Plus, shooting with one stock just kept things simple logistically.”

A scene from director Adrian Shergold’s feature "Cordelia." Copyright Cordelia/StudioPOW Limited.

In order to heighten the grain and contrast in the image Slater Ling had the negative push-processed by one stop at the lab. This, along with frequent under exposure of the image delivered a final picture with “beautiful saturation, enhanced texture and lovely inky blacks.”

Film development and 4K scanning was supervised by Martin McGlone of Kodak Film Lab, which is based on the lot at Pinewood Studios.

To help portray menace and amplify tension in certain scenes, the DP employed the classic technique of using split-field dioptres in front of the lens to keep subjects in both foreground and background in focus in the same frame - such as a close-up on a ringing telephone with Cordelia in the distance.

BTS of the crew during production on director Adrian Shergold’s feature "Cordelia:" (l-r) Graham Drover 1st AC, Amber Osborne clapper/loader, and grip Rupert Lloyd Parry. Photo by Kerry Brown. Copyright Cordelia/StudioPOW Limited.

The movie also features a number of long, sinuous takes, as the camera follows Cordelia around the confines of her apartment. These were developed with the assistance of grip Rupert Lloyd Parry, who suggested the use of a remote head, operated by Slater Ling, fitted on a dolly that tracked over flat boards to give fluidity and stability.

To light these scenes gaffer Paul Murphy created soft-boxed top lights around the entire set, using Sky Panel 60s, with 5Ks, 2Ks and Par lamps placed around the softbox edges, under which were unbleached muslins as ceiling pieces. The ceiling was flagged off from above to keep the edges dark and most of the light off the walls. All practicals had Tungsten bulbs except the bathrooms, which had traditional fluorescent 4300Kelvin tubes gelled with ¼ green and ¼ blue for night. Outside the set were a range of LED spacelights, Sky Panels, LED Fresnels, with M40 HMIs for punch, plus more Pars and 2K’s gelled to match the exterior street lights on location. All of the lighting fixtures were wired to a dimmer board, operated by Jordon Brown.

BTS shot with director Adrian Shergold (r) during production on "Cordelia." Photo by Kerry Brown. Copyright Cordelia/StudioPOW Limited.

“The lighting set-up allowed for free camera movement throughout the set and enabled me to control the illumination levels in each room, change levels on the move, and to rapidly adjust the ambience between day and night scenes,” says Slater Ling. “Also the LEDs are great for changing color and color temperatures very quickly, which enabled me to make the most of color contrasts on the 35mm film.”

Slater Ling conducted the final grade with colourist Michelle Cort at Twickenham Studios’ post-production facility. “During post, the main work was making sure we matched daylight scenes together, and I added a little blue to the dark and shadow areas of the images to support the discomforting feeling of the aesthetic.

DP Tony Slater Ling BSC at the 35mm film camera during production on director Adrian Shergold’s feature "Cordelia." Photo by Kerry Brown. Copyright Cordelia/StudioPOW Limited.

“But beyond that, I was incredibly impressed by how amazingly flexible film is across so many different situations and subject matters: its latitude and forgiveness in scenes with dark shadows and bright highlights; its capabilities in available light; and its beautiful, creamy quality on the skin tones. In digital, we often use old lenses and diffusion in order to get the same pleasing skin tones and textures that you get naturally on film emulsion right from the start.”

Slater Ling adds: “I really enjoyed coming back to shooting on film with a small camera crew. It was liberating to be free from the behemoth of the video village, as well as the monitors and cabling that come with it. The final result, with its texture and colors, looks absorbing, alive and vivid, and I can’t wait for people to see it on the big screen.”