'A Quiet Place' stuns audiences and delivers stunning box office receipts

John Krasinski plays Lee Abbott in "A QUIET PLACE", from Paramount Pictures.

Shot on Kodak 35mm film, the suspenseful horror feature A Quiet Place earned fearsome acclaim worldwide when it released in April 2018 and has since put in a frighteningly good performance at the global box office, too.

Following an unspecified ecological disaster that has wiped out most of the human population, the Abbott family – husband Lee, wife Evelyn, congenitally deaf daughter Regan, and sons Marcus and Beau – are forced to survive in silence as they try to elude giant, sightless reptilian predators that locate their prey via ultra-sensitive hearing. Leaving their safe house bunker to scavenge for supplies, the family converse in sign language, knowing that even the slightest sound will alert the killer creatures.

John Krasinski plays Lee Abbott in "A QUIET PLACE", from Paramount Pictures.

The movie was directed and co-written by John Krasinski, who also stars in the film alongside his real-life spouse Emily Blunt. It has returned almost 20 times its original $17 million budget, with about $321 million in box office receipts. The total continues to rise as the film is still playing in theatres around the world, with online, Blu-ray and DVD releases still to come.

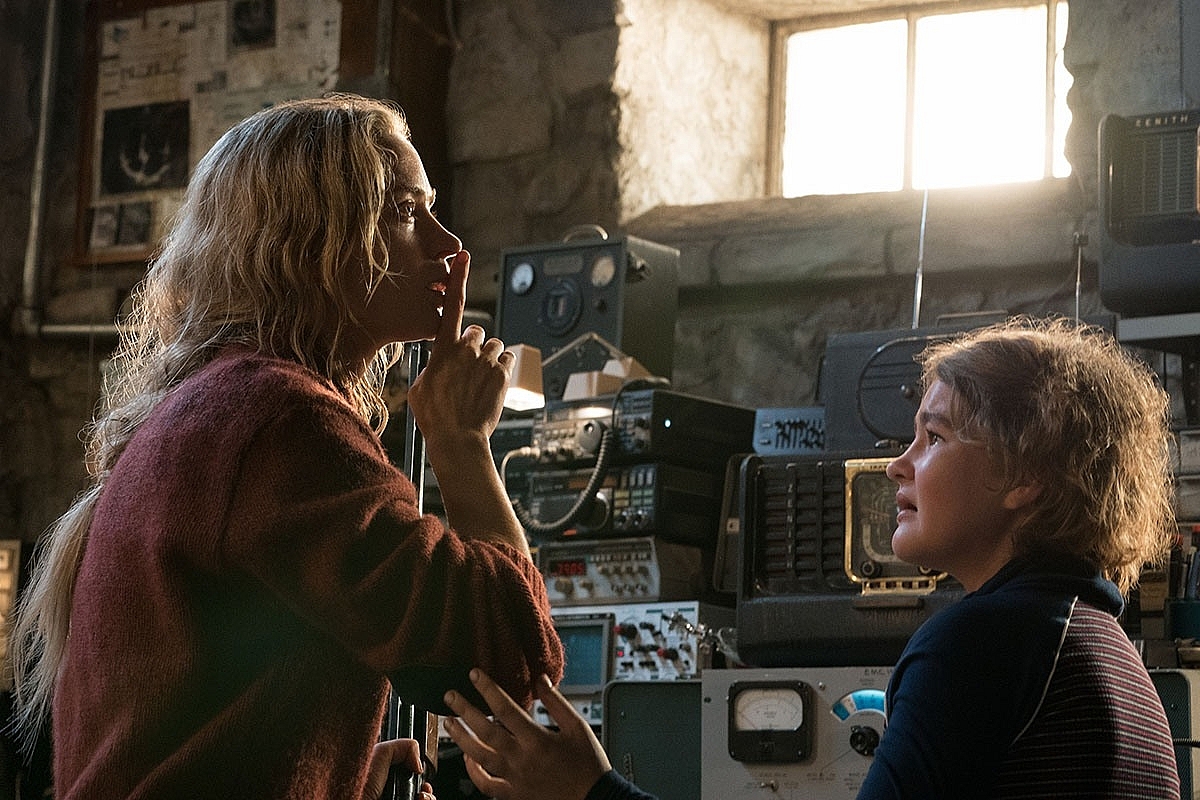

Left to right: Emily Blunt and Millicent Simmonds in "A QUIET PLACE", from Paramount Pictures.

Hailed by critics as a” brilliantly suspenseful,” “back-to-basics thriller,” A Quiet Place was shot by cinematographer Charlotte Bruus Christensen DFF, whose previous features on film include the 35mm-originated productions of Far From The Madding Crowd (2015), Fences (2016) and The Girl On The Train (2016). Filming took place over 30 days at the end of Summer 2017 in verdant rural locations in the Dutchess, Ulster and Herkimer counties of Upstate New York. As is her wont, Bruus Christensen operated A-camera, with David Emmerichs shooting B-camera and second unit photography. The gaffer was Bill Almeida.

Left to right: Noah Jupe plays Marcus Abbott and John Krasinski plays Lee Abbott in "A QUIET PLACE", from Paramount Pictures.

“We all thought we’d made a good movie, but had no idea that it would become such a runaway success,” recalls Bruus Christensen. “I think that among the many reasons for this success were that we created a real, believable and tangible world from which the horror genre could emerge, while also defining a family and the bonds of love that are needed to preserve it. As the mother says, ‘Who are we if we can't protect our children?’”

A key challenge for the cinematographer was how best to create visuals for a movie that had precious little dialogue, which the sound designers could then take to make audiences feel as if they were right there with the family.

Left to right: Director/Writer/Executive Producer John Krasinski, Emily Blunt and Noah Jupe on the set of "A QUIET PLACE", from Paramount Pictures.

“John wanted the film to have a nostalgic, widescreen, Western-style feel, portraying the natural beauty of the outdoor landscapes as well as the daily routines of the family,” she says. “But I realised early on that along with the overall look, part of the visual language was how the audience would perceive sounds dependent on the distance of the camera to the characters or objects. Sometimes we had to be really close to the subject matter and noises would be audible – such as bare-feet stepping nervously across floorboards, or counters being moved around a Monopoly boardgame. At other times the camera would be further away, and any sounds would be out of earshot.”

Director/Writer/Executive Producer John Krasinski on the set of "A QUIET PLACE", from Paramount Pictures.

She adds: “However, the close focus on Anamorphics isn’t that good. Additionally, we had a lot of scenes set in low-light – in the family safe house and a big night exterior sequence set in a cornfield. I like to shoot at around a T5.6 when using Anamorphics, but that was going to be tricky shooting at night.”

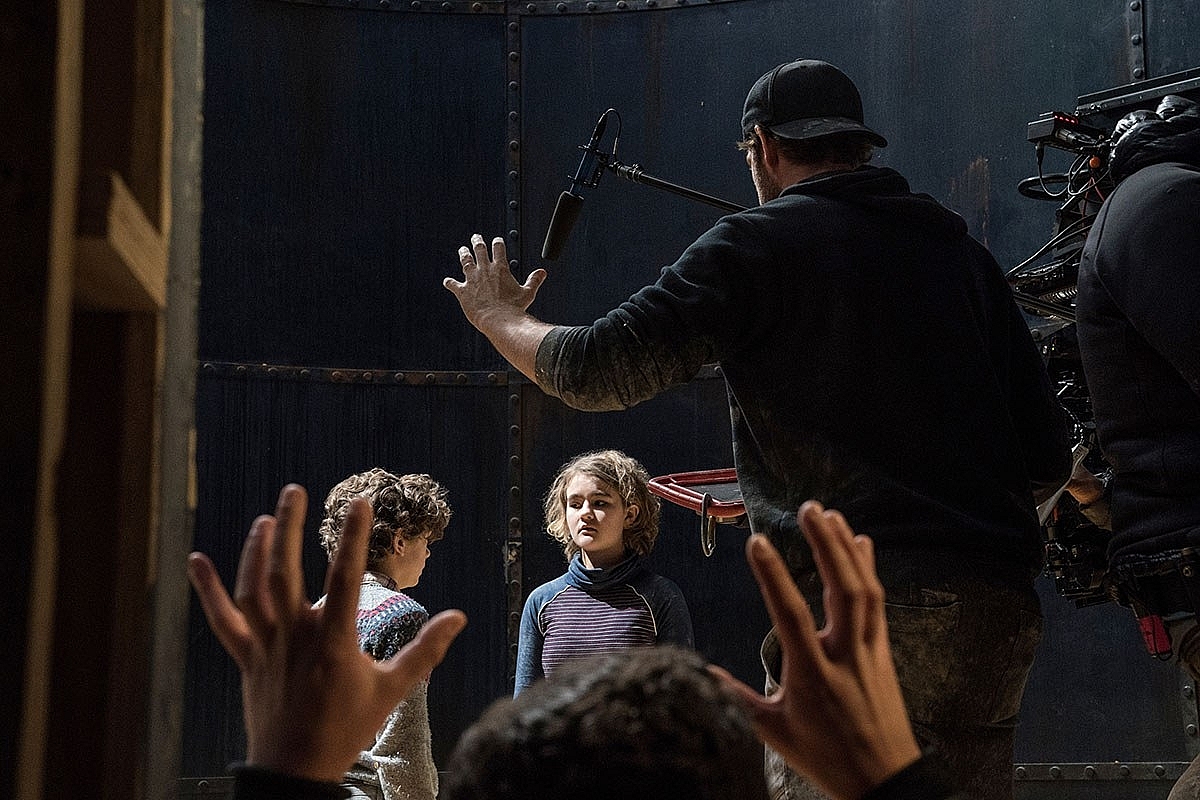

Left to right: Millicent Simmonds and Noah Jupe in "A QUIET PLACE", from Paramount Pictures.

Consequently, during prep Bruus Christensen sought out the lens expertise of Dan Sasaki and David Dodson at Panavision Woodland Hills. To shoot the film’s more conventional scenes, Christensen leaned towards the Panavision C-series Anamorphics, but went with T-series glass that was specially adapted and softened to match the C-series glass when closer focus was required. She employed faster Zeiss Super Speed spherical lenses for night exteriors/interiors and when the visual storytelling called for more physical closeness.

“Panavision worked on every single lens we used, and I cannot understate my thanks to them in making up a set that was just perfect for what I needed,” she exclaims.

Left to right: Noah Jupe, Millicent Simmonds and Director/Writer/Executive Producer John Krasinski on the set of "A QUIET PLACE", from Paramount Pictures.

If ever there was a project where a cinematographer might be sorely tempted to shoot digital, A Quiet Place was it – with extensive VFX and CG creature work, plus plenty of night exteriors in open spaces. However, Bruus Christensen says it was always her wish to capture all of the action on 35mm film. She was supported foursquare by Krasinski in her pursuit of celluloid production, and says together they made a strong case for film’s affordability to the producers. “I also checked in with Industrial Light & Magic visual-effects supervisor Scott Farrar about whether he foresaw any issues in shooting the VFX sequences on film,” she notes, “but he said 35mm would be absolutely fine.”

Emily Blunt in "A QUIET PLACE", from Paramount Pictures.

Curiously, all of the references Krasinski had for the look of the movie – Jaws (1975, dir. Steven Spielberg, DP Bill Butler ASC), No Country For Old Men (2007, dirs. Joel & Ethen Coen, DP Roger Deakins BSC ASC), There Will Be Blood (2007, dir. Paul Thomas Anderson, DP Robert Elswit ASC), and Let The Right One In (dir. Tomas Alfredson, DP Hoyte Van Hoytema FNF NSC) – were all shot on 35mm film.

“These are all great examples of slow, confident and suspenseful storytelling, with a composed camera that is always in the right place,” says Bruus Christensen. “In each of these, film automatically invites you into a relatable, truthful world out of which the horror genre emerges and the tension gradually ratchets up. Film captures the natural warmth, color and beauty of the daylight, but it’s also wonderful in the dark, the way it renders the light on a face from a candle, before falling off into deep detailed blacks. It is quite simply beautiful and uniquely atmospheric.”

Left to right: Noah Jupe and Millicent Simmonds in "A QUIET PLACE", from Paramount Pictures.

Bruus Christensen settled on three KODAK VISION3 Color Negative Film stocks for A Quiet Place: 500T 5219 for the night work, 50D 5203 for day exteriors, and 250D 5207 for day interiors and overcast day exteriors. Film processing was done at Kodak Film Lab New York.

“The 50D is a beautiful, slow, rich filmstock that naturally absorbs the warmth of the colors that are in front of the camera. I used it whenever we had sunlight during our day exteriors and knew it would match well with the scenes shot using the 250D,” she remarks.

Left to right: Noah Jupe plays Marcus Abbott, John Krasinski plays Lee Abbott, Emily Blunt plays Evelyn Abbott and Millicent Simmonds plays Regan Abbott in "A QUIET PLACE", from Paramount Pictures.

“The 500T never ceases to amaze me in the way that it has the dynamic range to photograph both blacks and highlights with interesting textures and details, in the same frame. The final third of the film is set in a cornfield at night, in the middle of nowhere, with no visible sources of light. The producers thought it was a little crazy to shoot that on film and wondered why I didn’t want to shoot digital. In that situation it was more about the spread of the light, rather than the intensity of light, and we would have needed large lighting fixtures in either case. Whether I was lighting for the 500T stock or the 800 ASA of a digital sensor, it wasn’t going to make much difference, and the results on film looked great.”

She concludes: “I love the analog way of working – just using my light meter, sitting beside the camera, observing the light on the actors and the scene in front of me. As there’s no video village, the on-set communication of the vision was really between me and my director. Working this way, I feel we really captured a visual look that adds to the understanding of a loving family in perilous circumstances. And the result definitely darker and blacker than I would have been allowed had we shot digital.”